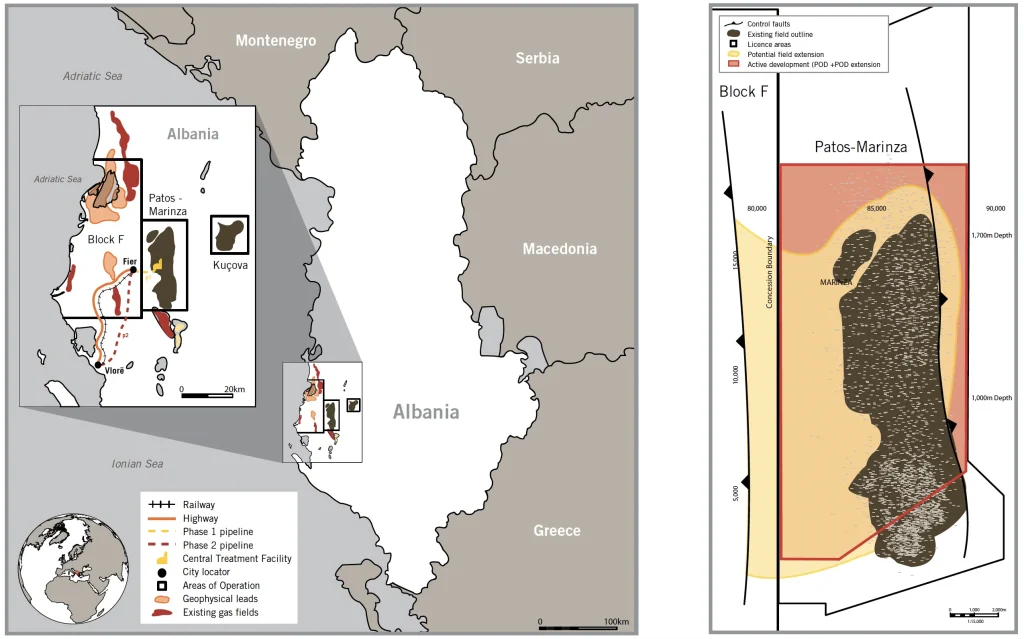

Bankers Petroleum Albania—operator of the Patos-Marinzë oilfield—has been hit by a fast-moving convergence of crises that now threatens both output and stability in one of Albania’s most strategic industrial zones. Within the space of roughly 24 hours, the company’s production activity was effectively frozen by customs authorities, while workers and subcontractors intensified protests over pay and working conditions, raising fears of a wider operational breakdown and renewed political escalation.

Customs blockade stops extraction at Patos-Marinzë

The most immediate shock came from the General Directorate of Customs, which—according to multiple Albanian media reports citing the company—ordered the blocking of Bankers Petroleum’s production and financial activity at the Patos-Marinzë extraction facilities. The stated trigger is an excise-tax dispute tied to the “diluent” used in heavy-oil production: customs authorities argue the company has not paid excise obligations for this input.

Bankers Petroleum’s response frames the action as arbitrary and procedurally unlawful, arguing that the diluent should not be subject to excise because it is not consumed in Albania and is used as a technical input in extracting and transporting crude that is exported. The company also points to a long-running legal conflict over this same issue, describing it as a matter still in court rather than one that should be enforced via an immediate operational shutdown.

Report TV links the current enforcement move to a much larger historical penalty: a fine totaling €120 million, reportedly assessed in 2019 after a customs investigation concluded Bankers had avoided at least €30 million in excise obligations related to diluent, with a further €90 million calculated as a penalty.

A technical shutdown with high-stakes consequences

Beyond the legal argument, Bankers and sector officials warn the stoppage is not a simple “pause.” Heavy crude at Patos-Marinzë requires continuous handling; once cooling begins, viscosity rises sharply and oil can solidify inside pipelines and storage infrastructure. In the company’s account—also quoted by Gazeta Shqip—Albania’s National Agency of Natural Resources (AKBN) has warned that extraction must run continuously (24/7) to avoid the crude becoming unusable in pipelines and tanks, and that storage constraints can force a full field shutdown with wider safety and environmental risks.

This is a critical point because it redefines the customs decision from a financial enforcement measure into an operational hazard: if the field is shut in abruptly, restarting can be technically difficult, expensive, and in some wells impossible—an argument Bankers uses to portray the blockade as disproportionately damaging to the Albanian state as resource owner, not only to the operator.

Labour unrest: “unpaid November” and a protest that is no longer isolated

While the customs dispute escalated at the institutional level, the social front has also heated up. The protest on 16 December 2025 did not appear in a vacuum. Earlier reporting through 2025 describes repeated mobilisations—demands for wage increases, implementation of collective agreements, improved working conditions, and recognition of oil-worker status. In October, workers were also reported to have entered a hunger strike, urging the state to mediate more actively. Bankers, for its part, previously acknowledged industrial action and union pressure but insisted production had continued normally during the strike period and pointed to planned increases in allowances while rejecting further wage hikes due to “financial pressures,” including oil-price weakness and exchange-rate effects. The risk is that each pressure point amplifies the other: when workers fear wages are at risk, a state-ordered shutdown looks like confirmation; when the state sees instability, enforcement can harden.

A broader legal cloud hangs over the operator

Layered onto the operational and labour crisis is an expanding legal narrative around Bankers Petroleum’s finances.

Albania’s Prosecutor’s Office in Fier described an investigation alleging Bankers Petroleum Albania Ltd engaged in fraudulent schemes related to VAT, concealment of income, money laundering, and other offenses, with precautionary measures taken against multiple individuals and others declared wanted. The same source release claims the company reported losses consistently from 2004 through 2024, despite large volumes of exports and domestic sales, and alleges damages to the state budget linked particularly to fraudulent VAT claims.

This backdrop matters because it shapes how every new development is interpreted. For critics, the customs blockade and wage protests reinforce a narrative of a politically protected operator now facing overdue accountability. For the company, aggressive enforcement is portrayed as premature, legally questionable, and capable of destroying assets that ultimately belong to the Albanian public.

What is happening now—and what happens next

As of 16 December 2025, the situation around Bankers Petroleum can be summarised as a three-front confrontation:

-

Institutional enforcement: Customs has moved to block operations over a contested excise obligation tied to diluent, with references in reporting to a much larger unresolved fine dating back to 2019.

-

Operational risk: AKBN warnings cited in media coverage underline that halting heavy-oil production can cause technical damage and safety risks if the system is not managed carefully.

-

Workforce instability: Protests and claims of unpaid wages—especially among subcontractors—indicate growing social stress at the field level, with political actors amplifying the message and demanding state intervention.

The immediate next steps are likely to unfold across institutions rather than at the wellhead: pressure on the Ministry of Finance to intervene, continued court and prosecutorial actions, and negotiations (formal or informal) over how the field can be kept safe and technically stable while legal disputes continue. The deeper question—still unresolved—is whether Albania’s largest onshore oil operation can sustain output and social peace while sitting at the intersection of labour conflict, tax enforcement, and criminal investigation.

If the blockade persists, the costs will not be measured only in barrels lost, but also in jobs, contractor liquidity, community safety, and the credibility of the state’s ability to regulate strategically vital assets without triggering destabilising shocks.