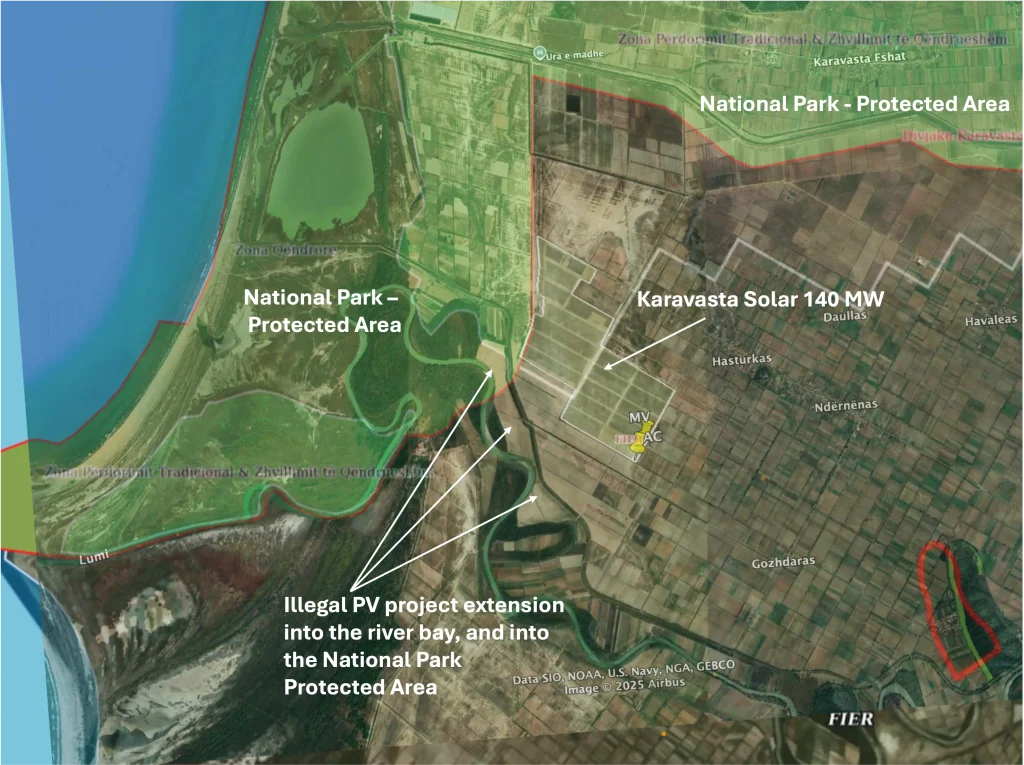

The Ministry of Infrastructure and Energy of Albania signed the Project Development Agreement with Voltalia for the construction of the photovoltaic plant in Remas – Karavasta (near the Lushnja area) with an installed capacity of 140 MW, where the power generation from 70 MW will be offered as part of the support measures at a price of 24.89 euros/Mwh to state owned company ( OSHEE GROUP , public company) for 15 years and 70 MW will be traded on the free market, supported by EBRD with 33M Euro loan. The Karavasta Solar Park entered production in January 2024.

The concession agreement in question leaves numerous concerns unsettled. Beyond its significant social and environmental consequences—strongly opposed by local communities due to its proximity to the Divjaka-Karavasta National Park—the project represents Voltalia’s expanding and contentious presence in Albania. This development looks to follow the trend of so-called “green” efforts in the country, which have long been marred by suspicions of green corruption.

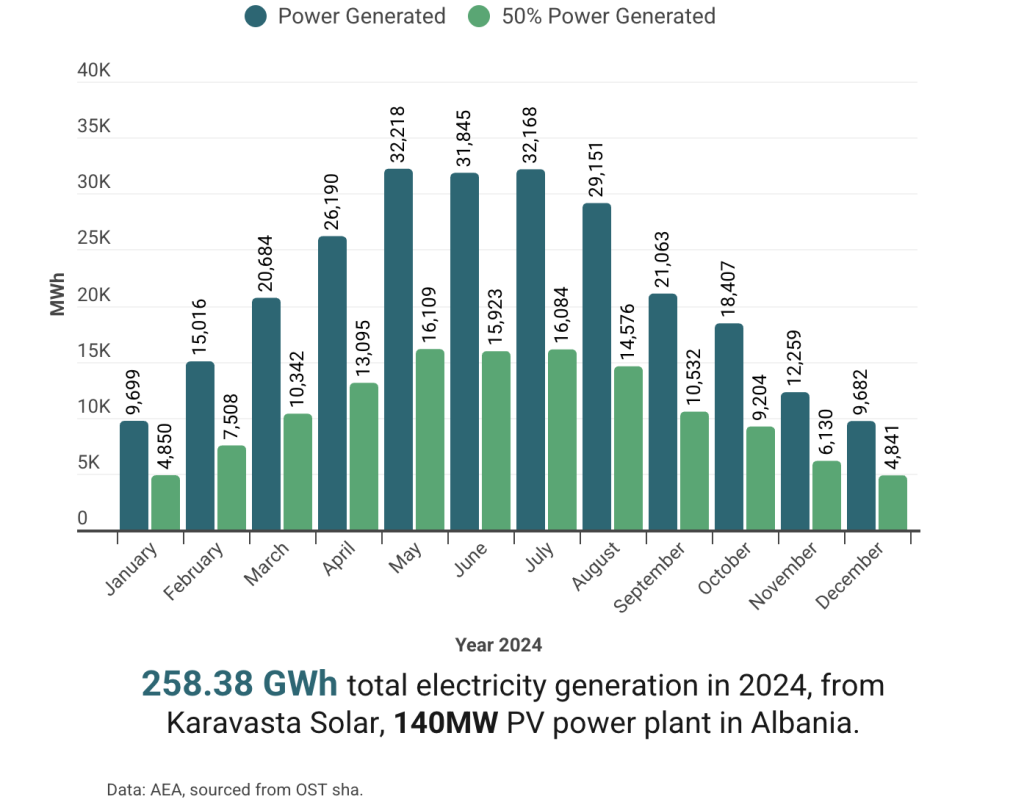

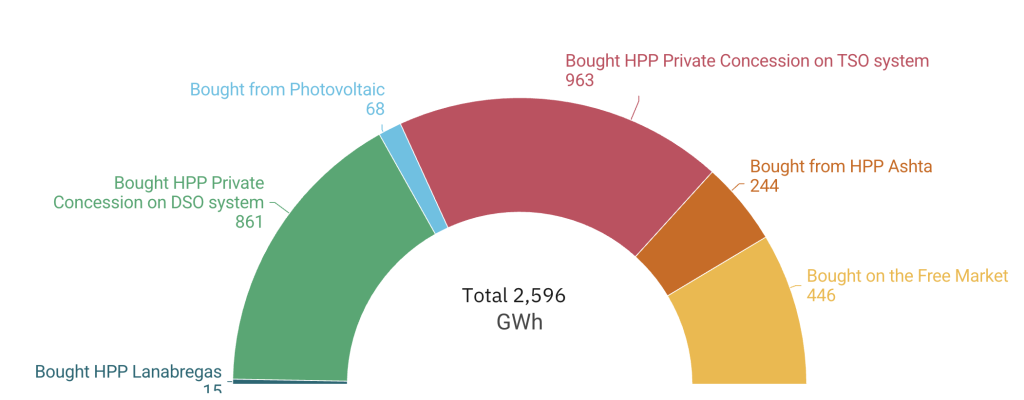

For 2024, the Karavasta solar power plant reported total electricity generation of 258.38 GWh. Yet the Energy Regulator Authority’s (ERE) report does not disclose the destination of roughly half of that output — 129.19 GWh — which should be sold under a contractual tariff of €24.89/MWh (towards OSHEE group). That unexplained 50% gap in the balancing is striking. The same report shows that FTL sh.a the Free Market Supplier, purchased only 67.7 GWh from domestic photovoltaic producers, while the other amount of the total of 2,596 GWh were supplied including hydropower generation and purchased on the free market. Taken together, these figures reveal inconsistencies in market reporting and raise serious questions about transparency, corruption, contractual compliance, and the adequacy of regulatory oversight.

The Karavasta Solar PV plant site is adjacent to Divjaka-Karavasta National Park, a Candidate Emerald Site under the Bern Convention encompassing Karavasta Lagoon Ramsar Site. The project site also partially overlaps with the Karavasta Lagoon Key Biodiversity Area (KBA) and Important Bird Area (IBA) designated for globally threatened bird species, important congregations of wintering and breeding waterbirds, and the endemic Albanian Water Frog.

In the case of the Spitalla Solar project, Voltalia SA has proceeded with internal procurement tenders and is preparing to begun construction of the high-voltage lines, a substation bay, and the plant itself, despite failing to provide formal communication to stakeholders or local residents. No environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA), restoration plan, or archaeological survey has been presented, nor has any meaningful public hearing been conducted to date. The company is reportedly working with a well-connected local firm linked to government and political circles to produce the required reports and assessments—documents that, critics allege, exist largely on paper. Local communities, facing limited possibilities for recourse, describe the project as shielded by a network of political protection and systemic corruption.

Voltalia SA has established two local businesses — “Spitalla Solar” and “Karavasta Solar” — through its Dutch vehicle, Voltalia Management International B.V., which is registered in a country that may hinder transparency. Spitalla Solar has two foreign administrators, Bertrand Pierre Francis Tournier and Gustavo Manuel Ferreira Fernandes; the same people also run Karavasta Solar, the concessionaire for the Karavasta solar park, which has a 30-year concession. The fact that both Albanian companies are subsidiaries of a Dutch holding company raises valid concerns regarding ultimate beneficial ownership, corporate transparency, and regulatory control.

It appears that Prime Minister Rama may have steered these projects toward associates tied to President Macron — a move critics describe as a political favour rather than a transparent procurement outcome. The 2020 Albanian Law on the Beneficial Ownership Registry was intended to reveal company shareholders, but its 25% disclosure threshold leaves room for concealing minority owners; consequently, a convicted individual or someone embedded in politics could remain undeclared if they hold under 25% of a company’s shares, even when that company wins public contracts. The planned 100 MW photovoltaic park is covered to be developed alongside the new Durrës Port and the Reconstruction zone — developments likely to reshape the local real-estate market. In this sensitive corridor, a French firm and a Dutch entity with opaque ownership structures were granted 121 hectares by the government for 30 years, a deal that raises serious questions about transparency, accountability and the protection of the public interest.

The financial advantages and drawbacks of concession agreements, compared to new production capacity outside such arrangements, are closely tied to contractual provisions defining the allocation of financial risk. According to a statement by Voltalia SA, concession contracts can shift this burden onto the Albanian state budget, effectively exposing public finances to potential liabilities—often without the public’s awareness.

By Ranier della Vecchia