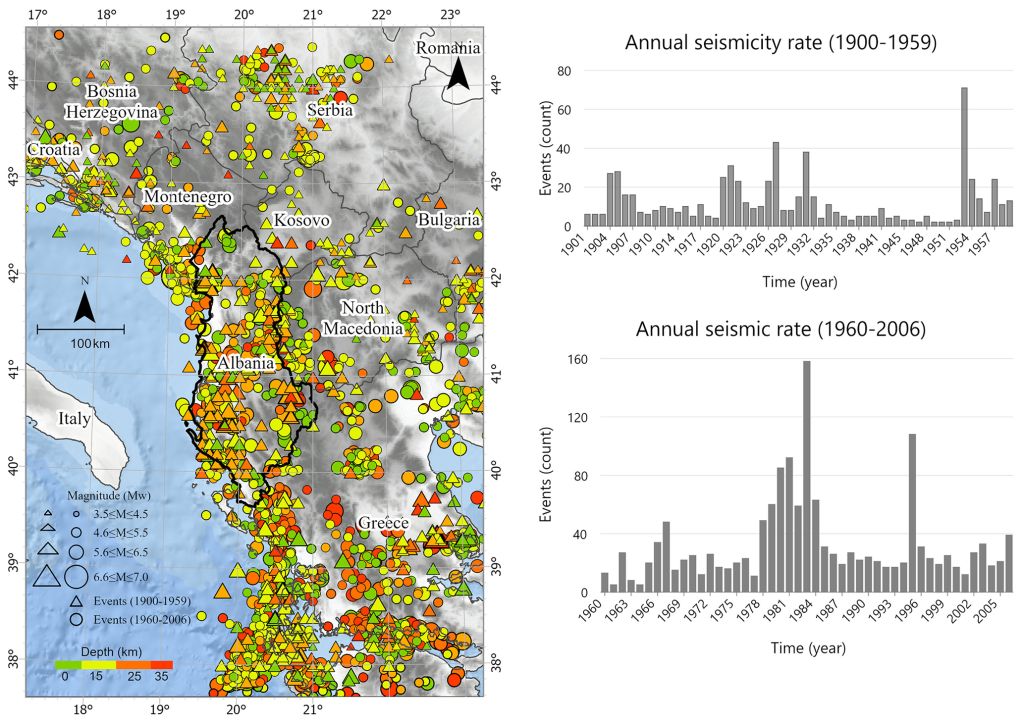

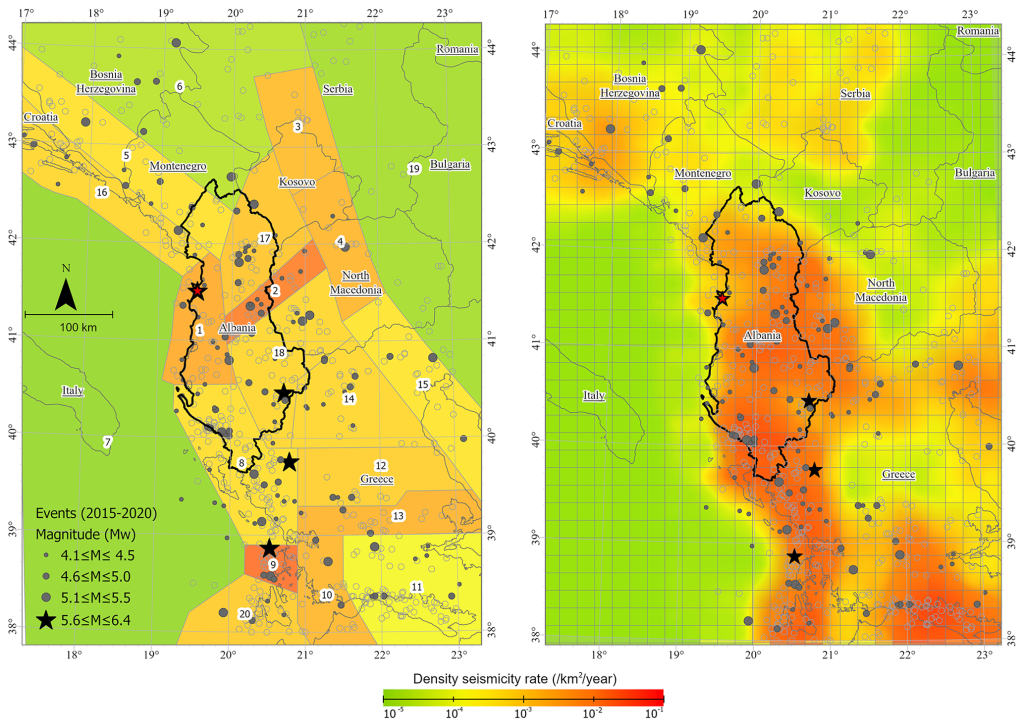

Albania, which is located in a very active seismic zone, is always at risk of an earthquake. The severe shocks of recent years have underlined the vital need for strong disaster preparedness and resilient financial systems. Historically, the burden of post-disaster rehabilitation has fallen mostly on the state budget and international aid, a model that is fundamentally unsustainable and frequently inequitable in the long run. This legislative initiative seeks to establish a mandatory insurance scheme for residential properties, concurrently creating a dedicated “Fondi Kombëtar për Sigurimin e Detyrueshëm nga Tërmetet” (National Compulsory Earthquake Insurance Fund) to manage associated risks and payouts.

A Solid Structure — With Cracks

The proposal establishes the National Earthquake Fund, a state-owned joint-stock firm with operational independence that is intended to pool risk, purchase reinsurance, and pay claims. Its governance is based on EU “hybrid” models, such as Turkey’s DASK and France’s CCR, in which the state underwrites catastrophic capacity while private actors handle risk pricing and distribution.

The inclusion of an obligatory insurance system in this draft law indicates a strategic shift in Albania’s approach to catastrophe management. Instead of relying solely on reactive measures, in which the state bears the majority of reconstruction costs following an earthquake, the government is transitioning to a system of pre-emptive risk transfer. This transition entails a concerted effort to promote financial self-sufficiency and lessen reliance on emergency budgets or external aid following a disaster.

Such a step might potentially create a more predictable and permanent funding source for recovery, freeing up state resources that would otherwise be committed to immediate relief activities and redirecting them into long-term prevention or other developmental programs. However, this fundamental shift means that citizens will now bear a portion of the financial burden for disaster recovery, demanding careful policy design to assure affordability and equity across all segments of the population.

Yet the scheme is narrow in one crucial respect: it covers only structural earthquake damage to houses, with exclusions as highlighted in “Article 6”, the law explicitly excludes :

- a) all bodily injuries including death;

- b) claims for compensation for moral damages;

- c) items within the premises of the insured property;

- d) expenses related to the removal and relocation of waste;

- e) financial losses from business interruption and lost profits.

These exclusions drastically limit the scope of the coverage. Most households place a high value on personal goods, which are crucial for returning to regular life following a tragedy. The expense of cleaning debris after a severe earthquake can be excessive, imposing an unexpected and often crushing financial load on already suffering homeowners. While the law primarily applies to residential structures, the exclusion of business interruption for sections of housing used as offices or sales units means that small businesses operating from residential premises would suffer severe financial disruption without compensation, impeding economic recovery at the micro level. This restrictive definition of coverage, which focuses nearly entirely on the building’s construction, ignores key aspects of post-disaster recovery.

This means that even with mandated insurance, afflicted families will still face significant out-of-pocket payments, perhaps leading to protracted hardship and reliance on other forms of assistance. This ultimately reduces the “holistic” financial resilience that the mandated program claims to provide. This is in direct contrast to schemes such as France’s CCR, which clearly includes “business interruption” plans and protects materials. Similarly, while Turkey’s DASK primarily protects the structure, additional private policies may cover contents and debris disposal.

The Heavy Hand of Enforcement

Perhaps the most controversial clause is Article 33: fail to pay your premium and you lose access to cadastral services, the e-Albania platform, and the National Business Center. This is not a fine; it’s a lock on essential civic and economic doors. Proponents call it an efficient compliance lever. Critics warn it’s disproportionate, especially for low-income families who might already struggle to pay.

The 2% deductible specified in Article 7.3 for “Pjesa e zbritshme” (the deductible) to be paid by the insured is also worth noting. While deductibles are a common element in insurance to discourage small claims and encourage risk management, a 2% deductible on the damage value (rather than the sum insured) could be significant, particularly for properties with high rebuilding costs.

This initial expense may provide a substantial barrier to initiating repairs for lower-income households or those facing extensive damage, especially when combined with the lengthy 9-month payback term. While this deductible is lower than Switzerland’s SPE (10% with a minimum of 50,000 Swiss francs), it is more than Spain’s CCS, which does not impose deductibles on residential properties. Turkey’s DASK also has a 2% deductible, however it is applied to the amount insured.

The 9-month payout timeframe stated in Article 11.4 for compensation payment raises serious concerns about speedy post-disaster recovery. This protracted duration might result in significant human and economic losses due to prolonged displacement and delayed reconstruction. It throws a significant strain on impacted individuals and families to find new accommodation and handle daily living expenditures for nearly a year, potentially driving them deeper into debt or poverty. Such a delay could also put a strain on public services and social support systems as they work to bridge the gap for affected residents.

The sanctions for noncompliance described in Article 33 (Zbatimi) are especially harsh and potentially unfair. According to the law, subjects who do not pay their premiums would be denied cadastral, e-Albania, and National Business Center (QKB) services. These are not only financial fines, but a denial of access to basic public and commercial services, which could jeopardize persons’ and enterprises’ capacity to operate legally and economically.

This is an especially aggressive and possibly unproductive enforcement strategy. Denying citizens access to e-Albania, the major gateway for different government services, effectively disconnects them from necessary interactions with the state. Blocking cadastral services halts crucial property transactions (sales and mortgages), putting individuals in legal uncertainty. Denying QKB services hinders business operations and registration. Such fines may disproportionately affect people who are already struggling financially, making it more difficult for them to earn a living, manage assets, or even receive social services, aggravating their economic vulnerability rather than promoting compliance.

It moves the burden of enforcement from established legal and financial channels to a broad administrative blockade, which may be interpreted as an infringement on fundamental civic engagement and economic activity. This method may result in a shadow market for property transactions or push vulnerable persons farther to the fringes, rather than integrating them into the insurance system.

While Article 5.3 specifies that the state budget will provide premiums for “social strata in need,” the “criteria and procedures” for this critical provision have yet to be decided by the Council of Ministers. Without clear, visible, and easily accessible instructions, the execution of this critical feature may be greatly delayed or subject to bureaucratic bottlenecks, potentially leaving the most vulnerable uninsured or facing further difficulty in receiving the essential subsidies. This lack of immediate detail need prompt explanation to assure the scheme’s true inclusiveness.

Europe’s Playbook: Broader Risks, Broader Pools

Compared to other European regimes, Albania’s focus looks almost too narrow:

- France and Spain bundle multiple natural perils — flood, fire, quake — into property policies, financing them through surcharges that spread cost across millions of policies.

- Greece: Law 5162/2024 primarily mandates natural disaster insurance for businesses with an annual turnover exceeding €500,000 and for vehicle owners. Business coverage requires a minimum of 70% of asset value (buildings, trucks, equipment, raw materials, products) to be insured against earthquake, flood, and wildfire. Crucially, the law does not explicitly mandate residential property insurance for all individuals.

- Italy’s new mandate targets companies, not households, but covers a broader disaster list, with a state reinsurer backing private carriers. A mandatory insurance for catastrophic events applies to corporate entities with registered offices in Italy. This covers fixed assets used for business operations, including land, buildings, plant, machinery, and industrial and commercial equipment. Covered events include floods, inundations, overflows, earthquakes, and landslides.

- Turkey (TCIP/DASK): Established in 2000, the Turkish Catastrophe Insurance Pool (TCIP/DASK) operates as a public institution responsible for mandatory earthquake insurance for homeowners. It provides financial security against earthquakes and related perils such as fire, explosion, landslide, and tsunami, primarily covering the building structure. T

By focusing just on earthquakes, Albania risks overlooking the larger financial picture: floods and fires are becoming more common, with disastrous economic and social implications. Leaving them out of the “mandatory” category risks creating a false sense of security—and a financing scramble after the next non-seismic disaster.

Public-Private, or Public-Public?

The Fund’s state ownership and tax breaks lean significantly toward a public monopoly. While the draft allows for the outsourcing of operations to an “International Technical Operator,” front-end sales and pricing are still established centrally. The EU’s experience demonstrates that retail competition, with the state acting as the last resort reinsurer, results in sharper pricing and better service. Without that competitive tension, premiums risk drifting upward while innovation stalls.

Albania’s draft law appears to be aiming for a hybrid model, combining the financial security and broad reach typically associated with a public entity, such as Turkey’s DASK, with the possibility of leveraging international expertise and risk diversification through private sector partnerships, similar to France’s state-backed CCR reinsurance model.

However, it carries the inherent risk of inheriting flaws from both models, including the potential for political influence often associated with public entities, as previously discussed, as well as the complexity and potentially high costs associated with integrating and overseeing international private operators. The eventual success of this hybrid model will be greatly influenced by the nature of these collaborations as well as the strength of the regulatory structure established to assure transparency, accountability, and defined responsibilities.

Financial Justification: Will Citizens Buy In?

Even with modest deductibles, citizens may perceive a one-hazard, state-driven policy to be of poor value, especially if it is obligatory. Voluntary systems with fiscal incentives, such as those used in Greece, can help to build public trust before implementing universal mandates. Linking coverage to various high-impact threats (quake, fire, and flood) makes the product more protective and appealing.

What Needs Rethinking

The future effectiveness and public acceptance of this effort will be heavily reliant on fixing many identified “fault cracks”:

- Expand the risk list to include high-cost occurrences like fire and flood, making the approach applicable year-round.

- Consider voluntary participation for households, at least initially, paired with tax incentives, while keeping mandatory rules for commercial and critical infrastructure.

- Expand coverage Scope: The existing exclusion of “contents within the building” and “debris removal costs” severely limits the policy’s broad coverage.

- Accelerate Payout Timelines: The 9-month payout term is too lengthy for immediate post-disaster recovery and may increase humanitarian situations. It should be a priority to emulate Turkey’s DASK, which strives for payments “usually within one month”.

- Refine Non-Compliance fines: The “digital exclusion” fines, which prohibit access to cadastral, e-Albania, and QKB services for nonpayment, are excessively punitive and may seriously impede socioeconomic participation. Consider alternate, less severe enforcement tools, such as financial penalties (akin to Greece’s business fines).

- Enhance Fund Independence and Transparency: While state oversight is unavoidable for a public organization, the Fund’s operational independence must be truly strong. Reviewing the Board composition to reduce perceived political influence, potentially by bringing in more independent experts or civil society representatives, could boost public trust.

- Clarify Role and Cost of International Operator: Greater transparency is needed regarding the expected costs and specific responsibilities of the “International Technical Operator”.

- Open the front-end to private competition — let licensed insurers sell the product under uniform terms, with the Fund as reinsurer.

- Integrate a prevention fund, à la France’s Barnier Fund, to link premiums directly to risk reduction projects.

The Stakes

Albania’s proposed law is more than just a policy suggestion; it’s a statement about how the country plans to manage risk in an era of catastrophic events. Its architecture is cleverly based on European models, but its narrow hazard scope, public monopoly leanings, and strict enforcement may weaken public support and long-term viability.

A seismic event will put Albania’s institutions to the test, as well as the strength of its buildings. If policymakers can expand coverage, open the market, and connect enforcement with social equality, this insurance program has the potential to become a model. If not, it may be regarded as a well-built building that provided insufficient protection, like the situation of the wildfires that is happening yearly in Albania and all Balkans.

The law: https://konsultimipublik.gov.al/Konsultime/Detaje/851

By: Erlet Shaqe