Legal Validity and Consistency

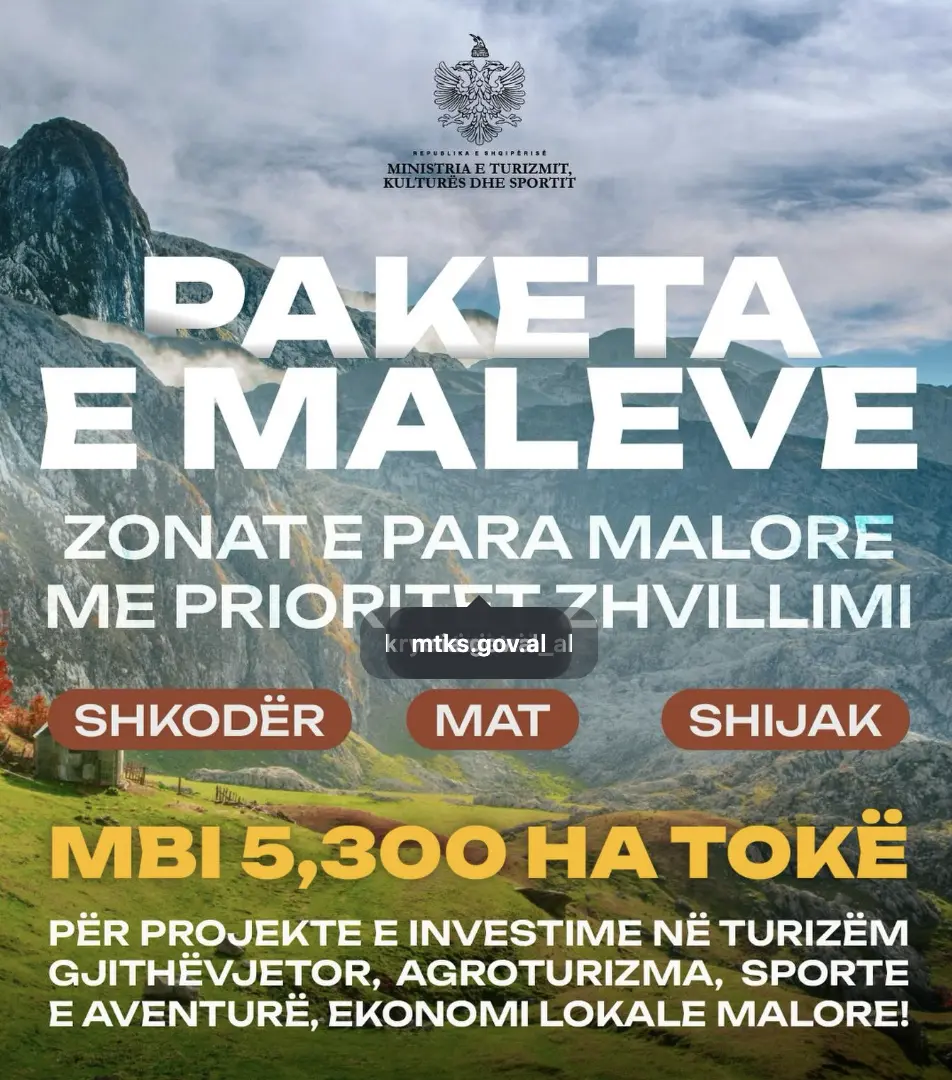

National Legal Framework: Law No. 20/2025 “Për Paketën e Maleve” was enacted by the Albanian Parliament pursuant to constitutional articles 78, 81(1), 83(1) and 155[1]. These references indicate the law was adopted in line with required legislative procedures and with due regard to constitutional provisions on property and fiscal matters. Notably, Article 155 of the Constitution mandates that taxes or exemptions must be established by law; indeed, the Mountain Package law includes targeted tax exemptions (for up to 500 beneficiaries) and thus appropriately anchors them in legislation[2][3]. By citing Article 155, the law acknowledges the need for a legal basis for fiscal incentives, suggesting formal consistency with the constitution’s requirements on public finances.

The law’s objective and scope are clearly defined in Articles 1 and 2. It aims to boost investment and economic/tourism development in mountainous areas through transfer of state-owned immovable property to “non-owner possessors” (individuals or entities who have long occupied the land without title) for a symbolic price, on the condition of sustainable investment in projects that stimulate the local economy[4][5]. This legislative solution addresses a longstanding challenge in Albania’s highlands: many occupants lack formal title due to historical and customary practices. By bridging customary land rights with formal legal ownership, the law seeks to integrate informal possessors into the legal framework[6]. Such an approach is innovative domestically, effectively transforming de facto possession into de jure ownership if certain criteria are met. It reflects an attempt to reconcile Albania’s customary property norms (e.g. family or clan-based claims in mountain regions) with statutory property law, a balance that is in principle permissible so long as it respects higher-ranking laws.

In terms of hierarchy, the law is an ordinary law but with elements that affect property rights, local governance, and taxation. It does not formally amend the constitution, but it must operate in harmony with constitutional principles such as equality before the law and protection of property. The mechanism it establishes – transferring state land for €1 in exchange for development – could raise questions under the constitutional right to property and equal treatment. However, because the land in question is state-owned and the transfer is voluntary by the state, it does not constitute an expropriation of someone’s private property. The law carefully excludes any lands that have existing private ownership claims or pending restitution decisions for former owners[7][8]. It requires municipal authorities and the Cadastre Agency (ASHK) to verify that each parcel is indeed state property, not subject to third-party property rights or prior legal processes (like the 2020 property legalization law)[9][10]. This safeguard is crucial for constitutional consistency: it helps prevent the state from inadvertently alienating land that rightfully belongs to someone else (such as an expropriated owner awaiting compensation). If this verification is diligently carried out, the law stays within the bounds of the state’s authority over its property.

Potential Ambiguities: Despite these safeguards, some legal ambiguities exist. One concern is how the law would handle a scenario where a rightful private owner of a parcel (or their heirs) comes forward after the 45-day public notice period and after the land has been transferred to a non-owner possessor[11][12]. The law provides a public transparency window for any third party to assert ownership claims before finalizing the transfer, and it mandates rejection of the request if valid title documents (even unregistered ones) are presented by a third party during that period[11][12]. However, if an owner fails to see the notice (e.g. diaspora heirs not reached in time), their property could be sold for €1 to the occupier. In such a case, the original owner might argue a violation of property rights. Albanian law would likely treat the transfer as valid (since the state believed it was disposing of its land), but the dispossessed owner could seek compensation from the state. This is a legal grey area: the law does not explicitly address compensation for post-factum claims. Albania’s obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights (Article 1, Protocol 1) require a fair balance when property is taken. Notably, the European Court of Human Rights has upheld that adverse possession regimes can be compatible with property rights so long as they serve the public interest and follow due process – for example, in J.A. Pye (Oxford) v. UK, the Grand Chamber found no violation where an owner lost land to a squatter under clear legal rules pursuing legitimate aims of land certainty[13]. The Mountain Package law similarly pursues a public interest (rural development and legal certainty) and provides a procedure for notice and challenge. Nonetheless, to fortify legal certainty, Albanian authorities may need to ensure that any overlooked rightful owners have recourse (possibly via the existing Property Compensation Fund) to avoid protracted disputes or human rights challenges.

Another area of ambiguity is the interaction with Albania’s Civil Code provisions on usucapion (prescriptive acquisition). The law explicitly allows that a non-owner possessor who does not develop the entire parcel can later seek recognition of ownership of the remaining land under the Civil Code once they meet its time requirements[14]. This implies the law creates a special, faster pathway to ownership for those willing to invest, while leaving others to the ordinary (and slower) adverse possession rules. There is no fundamental legal contradiction here, but it does establish a dual-track system. Courts and agencies will need to coordinate these processes to avoid confusion (for instance, ensuring that a possessor cannot simultaneously pursue both routes for the same land portion). The law’s transitional relationship with the 2020 legalization law (Law 20/2020) is also notable: it excludes land already adjudicated under that law, except if requests under that law were denied – in which case the Mountain Package offers a second chance[10]. This suggests a legislative intent to use the new law as a catch-all solution for cases that fell through the cracks of prior programs, reinforcing consistency in the broader legal framework for resolving informal property situations.

Compatibility with EU Law: Although Albania is not yet an EU member, it strives to align new laws with the EU acquis. The Mountain Package law touches on areas of EU relevance: property rights, competition/state aid, environmental protection, and regional development. On property rights and legal certainty, the approach of formalizing long-term possession is not per se incompatible with EU principles – property law remains largely national. Many EU countries allow adverse possession in some form, and the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights (Article 17) and Court of Justice (CJEU) jurisprudence have not prohibited such national schemes. The key is that the law must respect fundamental rights and general principles such as non-discrimination and proportionality. In this regard, the law is facially neutral (open to all qualifying possessors in designated zones) and serves a public interest (developing disadvantaged areas), which would likely be viewed as a legitimate objective.

However, a significant EU-law dimension is state aid and competition law. By transferring state assets (land) at a symbolic price of €1 and granting generous tax exemptions (no infrastructure impact tax, property tax, VAT, or profit tax for 10 years)[15], the law confers substantial economic advantages to the beneficiaries. In the EU, such measures would ordinarily be scrutinized under state aid rules (TFEU Article 107). The European Commission has consistently held that selling public land below market value or giving selective tax breaks can constitute state aid unless justified and approved under EU rules[16][17]. In practice, EU member states can implement regional aid schemes to promote development in less-developed areas, but these must abide by state aid regulations (e.g. falling under a Regional Aid Map or de minimis aid limits, or obtaining Commission approval for larger schemes). Were Albania an EU member, the Mountain Package’s blanket 1 € land transfers and 100% tax holidays for 10 years would almost certainly require notification to and approval by the European Commission, as they exceed typical aid intensity thresholds (especially the VAT exemption, which is unusual in EU practice). As a candidate country, Albania is committed under the Stabilisation and Association Agreement to approximate state aid rules, so it will likely need to ensure that by the time of EU accession, either this scheme has ended or is made compliant with EU law. In summary, the law’s incentives align with the goal of EU regional policy (reducing development disparities), but the means – large state subsidies – represent an outlier approach that would need to be reconciled with EU competition law standards[16].

Another compatibility aspect is environmental law. The Mountain Package law simplifies and accelerates development permissions in mountain zones: it allows the National Council of Territory and Water (KKTU) to approve development projects even if local spatial plans are absent or would normally prohibit construction in that area[18][19]. While this streamlining may spur investment, it must be balanced with Albania’s alignment to EU environmental directives. The law itself does not waive environmental permitting requirements – therefore, projects must still comply with the existing Albanian laws on Environmental Impact Assessment (which reflect Directive 2011/92/EU as amended) and on nature protection (aligned with the EU Habitats and Birds Directives). It will be crucial in implementation that no “fast-track” development permit under this law bypasses the need for an EIA or an appropriate assessment for protected habitats. EU law would not permit such bypass: for example, the EIA Directive requires that certain projects (e.g. tourist resorts above size thresholds, hydropower plants, wind farms, etc.) undergo an environmental assessment before approval, and the existence of a special development zone scheme does not exempt Albania from this obligation. The CJEU has repeatedly emphasized that economic development schemes must respect environmental procedures – national authorities cannot use special laws to avoid conducting required assessments or to contravene conservation rules (as seen in cases like Commission v. Germany (C-137/14) where expedited permitting rules were struck down for undermining the Habitats Directive). Accordingly, the Albanian government must ensure that KKTU approvals under this law are conditioned on full compliance with environmental law, including consulting environmental authorities, conducting EIAs, and respecting any protected areas. Notably, the law defines that forests, pastures, and meadows – land categories common in mountain zones – are not considered “non-transferable public property”, meaning they can be alienated under this scheme[20]. While this is consistent with Albania’s internal classification of public property, it raises a flag: many forest and pasture lands may host valuable ecosystems. The Albanian authorities should reconcile this with EU environmental expectations by perhaps excluding national parks, Natura 2000 candidate sites, or other critical habitats from eligible zones. In spirit, the law’s stated goals do include protecting the ecosystem and territorial values in mountain areas[21][22], but robust regulations and enforcement will determine whether those words translate into practice or conflict with EU environmental acquis.

Enforcement and Rule of Law: The law establishes a detailed procedure involving multiple institutions – local government units (municipalities and their councils), the State Cadastre, the Agency for Treatment of Property, line ministries, and the National Territorial Council. This multi-layered process (from municipal identification and public notice to central government approval and oversight) is designed to ensure transparency and legality. For example, municipalities must conduct on-site verification of each claim, coordinate with the Cadastre to check the land’s legal status, and post a 45-day public notice inviting objections[23][8]. Such steps are meant to reduce the risk of fraudulent claims or hidden ownership. If properly enforced, these requirements strengthen the law’s consistency with the rule of law principle – decisions will be based on evidence and subject to administrative appeal and judicial review (the law explicitly provides a right to appeal any administrative decision under it)[24].

A possible enforcement gap, however, lies in capacity and integrity. The effectiveness of this law will depend on local officials’ ability to identify genuine long-term possessors and resist any pressure to favor particular individuals. The criteria for being recognized as a posedues jopronar (non-owner possessor) include continuous, uninterrupted possession for at least 10 years, acting as if owner, or a proven familial link to the land if not physically using it[25][26]. Evidence can include tax records, utility bills, witness testimonies, photos, etc.[27]. The law even states that lack of written proof is not an automatic barrier as long as no contrary claims emerge[28], which is a fair approach in areas where formal records were scarce. Yet this flexibility also means officials must exercise sound judgment – ensuring that only bona fide cases are approved. The law’s consistency with good governance will be tested in its implementation: if enforcement is even-handed and thorough, the law could improve trust in formal institutions by legalizing rightful claims; if it is lax or corrupt, it could undermine the rule of law by effectively legalizing land grabbing by those with influence. Overall, the legal design is comprehensive, but continuous monitoring and possibly further clarifying regulations (some are already mandated, such as ministerial instructions within 6 months[29]) will be needed to resolve any ambiguities and ensure the law’s application remains consistent with higher laws and Albania’s EU-oriented reforms.

Comparative EU Analysis

Albania’s “Mountain Package” law is a novel approach, and comparing it with EU member states’ practices reveals both common goals and divergent methods. The overarching goal – fostering development in economically lagging mountainous or rural areas – is widely shared across Europe. Many EU countries have special policies or legislation for mountainous regions, but the instruments differ and the Albanian law is in some ways more far-reaching in its property provisions.

Italy: Italy has long recognized “zone montane” (mountain areas) as deserving special attention. Rather than one unified “mountain package” law, Italy’s approach has been through regional development programs, fiscal incentives, and local autonomy mechanisms. For instance, Italy established Comunità Montane (Mountain Communities) – cooperative bodies of mountain municipalities – to channel funds and manage services in highland areas. Tax incentives have also been used: businesses operating in certain disadvantaged southern or mountain areas have at times enjoyed tax credits or reduced corporate tax rates under EU-approved regional aid schemes. However, Italy does not have an equivalent to Albania’s mass transfer of state land to occupants. In Italy, public land sales or leases must typically follow public tender or market valuation to comply with laws and (for EU members) state aid rules[16]. Italy’s development programs have focused on grants and infrastructure investment rather than giving away land. One somewhat comparable Italian practice is the symbolic sale of derelict properties in depopulated villages (the famous “€1 houses” schemes), aimed at attracting newcomers to renovate abandoned homes. Those initiatives, however, involve private or municipal properties that are empty, not occupied lands, and buyers must invest in renovation under local government oversight. They share the Albanian law’s idea of exchanging a nominal price for promised investment, but on a much smaller scale and without the element of legitimizing an informal possessor.

In terms of land tenure legalization, Italy resolved most ownership issues decades ago, so it hasn’t needed a law bridging “customary” and legal ownership as Albania is doing. Adverse possession (usucapione) exists in Italy but notably cannot be invoked against state property designated as inalienable public domain (e.g. demanial assets like coastlines or certain forests). Italy’s legal tradition would generally require a formal act to transfer state land for development, often with compensation or in exchange for public benefit. Thus, Albania’s approach of a blanket €1 sale for development purposes is more radical. From a policy perspective, Italy might rely more on EU structural funds and national regional funds to stimulate mountain economies (for example, through the National Strategy for Inner Areas, which targets remote communities with investments in services and business support). Albania’s law tries to achieve a similar revival of remote areas but does so by leveraging dormant state land and the initiative of local possessors/investors, rather than primarily using public funds. This could be seen as Albania compensating for its more limited fiscal resources – instead of grants, it offers land and tax breaks as the incentive.

Slovenia: Slovenia is a smaller country with significant Alpine and karst regions. While it does not have a single “mountain law” akin to Albania’s, it integrates mountain area support into broader rural development and spatial planning policies. Under EU cohesion policy and CAP (Common Agricultural Policy) measures, Slovenia designates areas with natural constraints (which include most highland farming areas) and provides subsidies to farmers there. There have also been tax incentives; for example, in some Western Balkan countries influenced by past Yugoslav practices (including Slovenia’s region historically), businesses in mountain or hill areas have enjoyed reduced profit tax rates to encourage local employment[30]. One source notes that in certain cases “hill and mountain areas [have] a reduced profits tax rate (15%)” as an incentive[30]. Slovenia’s approach thus leans toward fiscal relief and EU-funded projects rather than property transfers.

On the matter of property rights, Slovenia underwent its post-socialist land reforms earlier and does not face large-scale informal occupation issues. State-owned lands (forests, etc.) are either protected or managed by state companies and are not handed to individuals outside of standard procedures. In fact, Slovenia has a strong regime of protected mountain areas (like Triglav National Park) where development is tightly controlled. If anything, Slovenia has been focusing on sustainable tourism in mountains (e.g. eco-tourism in the Julian Alps) and using EU cohesion funds to improve infrastructure in mountain resorts[31]. The Albanian law’s allowance to override local planning restrictions would be viewed cautiously in Slovenia – Slovenian law requires conformity with municipal spatial plans, and any major development in a pristine area would trigger strict environmental assessments. In summary, Slovenia aligns with EU norms by prioritizing environmental sustainability and using financial incentives within EU rules, rather than extraordinary measures to transfer land ownership.

Croatia: Croatia offers a particularly relevant comparison, as it has a dedicated law for underdeveloped areas including mountain regions. Croatia enacted an “Act on Hilly and Mountainous Areas” in 2002, aiming at demographic renewal and economic growth in those regions[32][33]. That law recognized about 45 municipalities as mountain areas and provided various incentives, such as tax relief, rights to use natural resources, and privileges in renting state land (e.g. for grazing or farming)[33]. For example, under that framework, residents or businesses could get reduced income tax or profit tax, and preferential access to lease of state-owned forest and agricultural land[33]. This is conceptually similar to Albania’s goals – encouraging use of local resources and giving economic advantages to mountain communities. Over time, however, Croatia’s law was partly rolled back or merged into broader regional development schemes. Many of its provisions were amended or deleted, especially as Croatia prepared to join the EU and had to streamline its state aid and regional policy measures[33]. By 2015, Croatia introduced a new law on “assisted areas” which folded mountain areas into a larger category of lagging regions, funded by both the state budget and EU funds[34][35]. One noteworthy aspect: Croatia’s incentives did not generally include selling state land for a token price; rather, the state would still own the land but might offer long-term leases or rights (e.g. free use of forests for picking non-timber products, or cheap leases for pastures)[36]. Direct sales were not a core feature, likely to avoid undermining property restitution or fair competition. Thus, Albania’s approach of outright transfer of ownership is an outlier; Croatia’s policies were more about concessions and financial aid.

Like Albania’s law, Croatia’s mountain area measures had an explicit budgetary cap – for instance, the government set aside a specific amount of money (e.g. HRK 95 million in 2019 for the assisted areas program)[34]. Albania’s law caps beneficiaries at 500 for the tax exemptions[3], which is a similar concept of limiting fiscal exposure. Another parallel is the demographic focus: both aim to stem out-migration. Albania explicitly hopes to encourage diaspora return to mountain regions by legalizing inherited family land and offering incentives to invest[37]. Croatia likewise aimed to “stimulate immigration” back to deserted hill villages[32]. The cultural contexts differ, but both recognize that without people, economic revival is moot.

Best Practices and Notable Deviations: In general, EU member states dealing with mountain development emphasize sustainable practices and transparency. Best practices include ensuring community involvement in projects, maintaining environmental safeguards, and using competitive processes for significant investments. For instance, if a large ski resort is to be built on public land in an EU country, it would typically go through a public tender or at least a rigorous concession process, alongside environmental and social impact assessments. The Albanian law deviates by simplifying investment initiation – a private arrangement between a recognized possessor and an investor can lead to a project, with approval centralized at the national level. This could cut red tape, but it also sidelines typical competitive bidding and local land-use planning processes. EU trends in spatial planning favor empowering local authorities and adhering to long-term development plans (in line with the European Spatial Development Perspective and national planning laws). Albania’s law temporarily recentralizes decision-making for these zones to the KKTU (which includes central government representatives), presumably to overcome local capacity issues or parochial constraints. This is a deviation from the decentralization principle that many EU countries follow, though it might be justified by the extraordinary goal of legalizing and activating idle lands.

On the positive side, the law’s goals align with EU policy trends like the Green Deal’s emphasis on sustainable rural development and the EU Mountain Strategy (the EU has supported initiatives like Euromontana and the Alpine and Carpathian Conventions, promoting balanced development of mountain areas). The integration of environmental protection language in the law[22] and its focus on “efficient use of natural resources” and “ecosystem protection”[21] mirror EU sustainable development rhetoric. Also, by insisting that investments be “sustainable” and in the public interest[38][39], the law theoretically echoes EU standards – the real test will be in implementation. In practice, if Albania enforces this law in line with EU best practices (transparent procedures, respect for environmental and social standards, and ensuring the aid is proportional and purpose-bound), the decree would be seen as broadly aligning with EU policy objectives (even if the method of property transfer is unusual). If instead the law results in circumventing standards or benefiting a narrow set of actors, it would be an outlier and face criticism.

Specific Sector Comparisons: In energy project development, EU countries like Italy, Croatia, and Slovenia have been streamlining permits for renewable energy, but always within the confines of EU law. For example, Italy and Croatia, under EU pressure to boost renewables, have identified “go-to areas” for solar/wind where permitting is faster, yet they must still carry out necessary environmental evaluations. Albania’s mountain law could facilitate small hydropower or wind projects in remote areas by removing local planning hurdles, which is in spirit similar to EU efforts to expedite renewables. However, the EU’s approach is to streamline without sacrificing the assessments – something Albania must heed.

In land use and property rights, Slovenia and Croatia dealt with formalizing property largely through one-time restitution and privatization processes in the 1990s. They did not face a scenario of extensive informal occupation of state land by locals (their social ownership systems were different). In Albania’s context, the persistence of informal possession in mountain areas is a legacy issue the EU is aware of – progress in property rights reform is monitored in Albania’s EU accession reports. The Mountain Package could score positively as a reform measure to finally register and title lands, thus improving the rule of law in property relations (a key EU criterion). But again, EU comparisons highlight that fairness and due process are paramount: any hint that the process is arbitrary or that it bypasses rightful owners would be seen as undermining property rights protection.

In conclusion, the decree’s approach is more aggressive and interventionist than what is typically seen in Italy, Slovenia, or Croatia, where incentives exist but within stricter confines. It aligns with EU-wide policy trends in its aims (rural revitalization, sustainable development, utilizing idle resources) but stands out in its execution (land grants and broad tax holidays). This divergence means Albania will need to calibrate the law’s implementation to ensure it ultimately converges with EU norms – for example, by tracking the aid given, maintaining transparency, and adapting any procedures that conflict with EU directives. If successful, the law might even offer a case study for other countries grappling with informal land use, but it will be judged against Europe’s standards of legality, transparency, and sustainability.

Corruption and Financial Crime Risk Assessment

Any program involving land allocation, construction permits, and tax breaks inherently carries corruption and financial crime risks, and the Mountain Package is no exception. A careful analysis suggests several potential vulnerabilities:

- Discretion and Regulatory Capture*: The process of designating a “priority development zone” is initiated by a municipality but ultimately approved by the national Council of Ministers[40]. This step could be *susceptible to political influence. There is a risk that powerful interests might lobby for certain areas to be declared development zones not purely on merit, but because they have an investment plan ready there. If an investor with political connections identifies a lucrative piece of state land (e.g. scenic lakeshore in a mountainous municipality), they might pressure for that area’s inclusion in the scheme. Since the types of activities allowed in a zone are set by the Council of Ministers’ decision[41], there is room for tailoring a zone to a particular project. Strong transparency measures are needed here – e.g. publicizing the justification for each zone and subjecting it to scrutiny – to prevent zones from being gerrymandered for private gain.

- Identification of Beneficiaries: The law relies on municipal officials to identify and verify non-owner possessors. This stage is at the heart of the law’s integrity. Local officials could be bribed or influenced to certify someone as a long-term possessor who in fact is not. For example, an outside investor could collude with a local individual to pose as the “occupant” of record. Because the reward – eventual ownership of land for €1 – is very attractive, there is a real risk of false claims of 10-year possession. The law mitigates this by requiring evidence and by enabling third parties to contest claims[27][11]. Yet in many remote areas, documentation may be scant and community ties strong; a determined group could fabricate affidavits or other proofs without an easy way to refute them unless someone locally speaks up. Nepotism is another danger: municipal councils ultimately approve the list of recognized possessors[42], so council members might favor relatives or local elites. This could marginalize genuinely deserving poor families in favor of better-connected individuals. To reduce this risk, a high level of oversight by central authorities or independent observers could be warranted, at least initially. The involvement of the Cadastre Agency and Property Agency in verifying land status[43][44] provides some cross-check, but their focus is on ownership history, not on whether the applicant truly occupied the land. Civil society monitoring and whistleblower channels could help ensure that “ghost” or opportunistic claimants are exposed.

- Bribery and Kickbacks: Once a possessor is recognized and obtains the rights, the subsequent steps – getting a development permit and then a construction permit from the KKTU – could become points where bribery occurs. Although the law centralizes permit approval to KKTU to ensure uniformity[19][45], large projects often invite corruption in permitting (e.g. to overlook certain technical conditions or to expedite approval). The risk is heightened if the KKTU operates behind closed doors. A non-transparent decision to grant a development permit for a project that might normally be illegal under local zoning could raise suspicions of under-the-table payments or political pressure. Likewise, the subsequent sale contract by the Ministry of Economy (selling the land for €1) must be above board – while the price is fixed, the timing and conditions (like verifying the investment agreement) could be areas where corruption intervenes (e.g. to bend rules on what qualifies as an adequate project).

- Money Laundering Risks*: Real estate and construction are globally recognized as high-risk sectors for money laundering[46][47]. The EU’s own assessments have flagged that “the real estate sector is also exposed to significant [money laundering] risks”* due to the complex transactions and involvement of various professionals[48][49]. The Mountain Package could inadvertently create new avenues for illicit money integration. By enabling the rapid acquisition of land and development rights, it might attract individuals or entities who seek to park or clean illicit funds in construction projects. For instance, a criminal organization could partner with a local “front” person who qualifies as a non-owner possessor, then invest large sums of cash into building a resort or lodge, thereby converting illicit cash into a tangible asset. The law’s generous tax exemptions (including VAT exemption) further complicate the financial trail, as VAT-free purchases and sales could be exploited to mask money flows. Cross-border illicit funds could also come into play: since “investor” is defined to include foreign legal persons as well[50], a shell company registered abroad could invest in a mountain project with less chance of local scrutiny. To mitigate this, Albania will need to rigorously enforce its anti-money laundering (AML) laws in these transactions – e.g. performing due diligence on investors’ beneficial owners, scrutinizing the source of large capital inflows, and monitoring unusual transactions. EU AML standards (as per the 4th and 5th AML Directives) require exactly that kind of vigilance[51][52]. Albanian banks and notaries involved in the land sale and construction financing will be obliged to flag suspicious activity. Still, the rural context might be seen as lower risk by compliance officers**, which is a mistake – in fact, a remote project can be an appealing way to launder money under the guise of legitimate rural investment. The government should consider involving the Albanian FIU (Financial Intelligence Unit) to provide guidance that these Mountain Package deals receive enhanced scrutiny due to their inherent risk profile (large cash investments, property transactions, foreign parties, etc.).

- Abuse of Discretion & Fraud: The law gives officials some discretionary leeway, for example in partially approving requests if only part of the land meets criteria[53] or in cancelling contracts if works don’t start in 3 years[54]. Discretion can be abused if not transparently exercised. An unscrupulous investor might bribe officials to overlook non-compliance – for instance, to not cancel a contract even if the project stalls beyond 3 years. Conversely, an honest investor could be shaken down by threats of cancellation. Clear regulations and external oversight (perhaps an audit of the program’s implementation each year) would help prevent such scenarios.

The public notice requirement is a positive anti-corruption measure, ensuring at least 45 days of visibility for each land claim[8]. This transparency can deter blatant fraud if, say, community members know someone is falsely claiming land – they have an opportunity to object. However, the effectiveness depends on local awareness and empowerment. If local populations distrust institutions or fear retribution, they may stay silent even if something improper is occurring. Here, involvement of NGOs or media to amplify these notices and follow up on contentious cases can provide an extra check.

- Land Valuation and Kickback Schemes: By design, the land is transferred at a symbolic €1, so there is no direct sale price to manipulate. This removes a common corruption vector (undervaluing land in sale for kickbacks). However, it could shift corruption to the post-transfer phase. Once the possessor-turned-owner has the land (after fulfilling conditions), they effectively hold an asset that could be quite valuable (especially with new infrastructure on it). They might then sell the developed property at full market value. If corrupt actors were involved, their profit is realized at this exit point. While this is more a profiteering risk than a classical corruption in public office, it is part of fraud risk: the scheme could be abused by speculators who pretend to undertake a long-term investment but plan only to flip the property after enjoying 10 years of tax holiday and increased land value. The law tries to counter pure speculation by requiring actual construction and use (no ownership transfer is final until the project is built and a usage certificate obtained[55]). It also voids the construction permit if works don’t begin in 2 years[56]. These are good safeguards. Nonetheless, after the project is completed and running for some time, nothing in the law stops the owner from selling it. At that stage, any illicit gains could be cashed out. One could envision, for instance, a corrupt official quietly backing a project, then benefiting from its sale through proxies. To reduce this, the law could have considered a longer-term claw-back or at least require that any transfer within the 10-year incentive period gets government consent (to avoid someone building a shell structure, getting the title, then selling immediately). Absent such a provision, oversight falls to general law – any fraud or corruption uncovered even after the fact could be prosecuted under criminal statutes, and the contract could potentially be voided if obtained by corruption (as it would violate public order). From a preventive stance, ensuring a robust audit trail for each project (documenting decisions, site inspections, progress reports, etc.) will make it harder for malfeasance to go unnoticed.

- Property and Land Conflict of Interest*: Another corruption risk lies in the *grey area of communal land. Many mountain communities traditionally share pastures or forests. The law allows an individual to claim such land if they can show personal possession. This could breed local corruption or conflict. For example, a village elder or local official might claim a pasture used by all villagers as if he alone “possessed” it, effectively privatizing a commons. If local authorities are complicit or stand to benefit (perhaps the claimant promises them a cut of eventual investor deals), they might certify this unjustly. This is partly a governance issue but also touches on ethical use of the law. It underscores the need for community consultation: before approving a claim, municipalities should verify that no other local families contest the “possession”. The 45-day public notice somewhat addresses this by giving any third party (including neighbors) the chance to object if, say, they also used the land. But communal usage rights are often informal and might not produce a single objector with legal standing. To guard against misuse here, the Ministry or Agency overseeing the program could issue guidelines that communal lands should be approached via community-based solutions (perhaps forming an association that can jointly benefit, rather than one person taking it all). Otherwise, perceived land grabbing by insiders could fuel corruption allegations and erode public trust.

- Alignment with EU AML/CFT Standards: It’s worth noting that as Albania aligns with EU AML/CFT (Anti-Money Laundering/Counter-Financing of Terrorism) standards, it will need to enforce requirements like customer due diligence for real estate transactions, reporting of suspicious transactions, and transparency of company ownership. The EU’s 5th AML Directive (2018/843) and 6th AML Directive emphasize these points[51][57]. Real estate professionals (notaries, lawyers, agents) are considered gatekeepers under these rules and must be vigilant[58][59]. In the Mountain Package context, when a sale contract for land is executed by the Ministry, a notary will formalize it – that notary should verify identities and funds per AML law. If the investor is a foreign company, Albania’s forthcoming Beneficial Ownership Register (an EU-inspired reform) should capture who ultimately controls it. The law itself is silent on these issues, so it relies on the general legal framework for AML and anti-corruption. Implementing agencies should incorporate checks (e.g., require a declaration of source of investment funds when applying for the €1 purchase) as part of the application dossier, to filter out suspicious money.

In summary, the Mountain Package creates opportunities for both well-intentioned development and ill-intentioned abuse. The main corruption risks – discretionary zone designation, false beneficiary claims, bribery in permitting, and collusion to misuse the scheme – are real but can be mitigated with strong governance measures. Transparency is the first line of defense: public notices, published lists of beneficiaries, open data on which investors get permits and tax breaks will allow media and civil society to spot anomalies. Accountability is the second line: clear avenues for complaint and appeal (which the law provides[24]) and active prosecution of any fraud or corruption (sending a message that abuse will be punished). If these checks are weak, the law could inadvertently facilitate land grabs, favoritism, and laundering of illicit capital – outcomes that would undermine its developmental intent. Conversely, if properly policed, the law can channel private investment into needy areas while maintaining integrity. Striking that balance is critical for public trust: communities must feel the process is fair and not just another vehicle for the well-connected to enrich themselves.

Sectoral Impact Analysis

The “Mountain Package” law will reverberate across multiple sectors. Key among these are Energy, Tourism/Investment, and the general sphere of land use and rural development. Below is an assessment of how the law could impact these sectors, including potential benefits and challenges:

Impact on the Energy Sector

Mountainous regions in Albania are rich in natural resources that lend themselves to energy projects – notably hydropower (mountain streams/rivers) and possibly wind or solar installations on ridges and plateaus. The law’s provisions can significantly influence how such projects come to fruition:

- Facilitated Site Acquisition: One historical barrier for energy developers has been securing land rights in remote areas, especially where ownership was unclear or fragmented. This law effectively opens the door for quicker site acquisition – an individual or family that has informally used a riverbank or hilltop can now get legal title and partner with an energy investor. By providing a legal pathway for local possessors to become landowners and then immediately granting development rights, the law reduces the transaction costs for energy companies. Instead of dealing with numerous squatters or municipal ownership issues, a company can team up with the recognized possessor to gain control of the needed land. This can accelerate projects like small hydropower plants or wind farms, aligning with Albania’s push for more domestic energy production (especially renewable energy). It’s worth noting that the government likely had renewable projects in mind, as indicated by the inclusion of the National Territorial Council “and Water” (KKTU) as the permitting authority[19]. The explicit reference to water in KKTU suggests attention to water-use permits, crucial for hydropower. By consolidating territorial and water approvals in one body for these zones, the law aims to streamline what used to be a multi-agency process.

- Licensing and Regulatory Oversight: While the law simplifies land and planning approval, it does not explicitly waive sector-specific licenses. Energy projects will still need to obtain generation licenses or concessions under Albania’s energy laws. For example, constructing a hydropower plant typically requires a concession agreement or license from the energy regulator or Ministry of Infrastructure. The risk is if investors interpret the Mountain Package as a fast-track that somehow sidesteps those requirements. Government should clarify that sectoral permits (energy, mining, etc.) remain fully applicable. If not, there could be legal confusion or attempts to shortcut proper licensing, which might conflict with EU energy acquis principles of fair competition and regulation. Assuming normal licensing remains in force, the law’s main effect is on speed and ease of getting the project to a shovel-ready state (land secured, development permit granted). This is in line with EU trends to streamline renewable energy deployment, but Albania must ensure non-discriminatory access – i.e., multiple investors could be interested in the same resource (say a river). Normally, a concession tender would decide who gets to use it. Under the Mountain Package, however, the investor who hooks up with the local possessor gets the inside track, potentially sidelining others. This raises a competition concern: to avoid perceptions of sweetheart deals, authorities could, for high-value energy sites, still run a competitive process or at least ensure the chosen investor offers commensurate benefits (technology, favorable power purchase terms, etc.) to the community or state.

- State Aid and Market Distortion: The incentives (free land, tax holidays) apply equally to energy investments. If, for instance, a small hydropower company builds a plant under this scheme, it could operate virtually tax-free for 10 years and with negligible land cost, whereas earlier projects not under this scheme had to pay taxes and land leases. This could distort the energy market by giving an advantage to projects under the scheme. From an EU perspective, as discussed, that looks like state aid which could affect market competition. In Albania’s current context, the power sector is partly liberalized, and many small hydros sell to the market or to the state utility at set tariffs. Those built under the Mountain Package might turn more profit due to lower costs, unless tariffs are adjusted. It will be important for regulators to monitor this and perhaps calibrate support schemes accordingly or limit the size of projects that can use the Mountain Package (the law does not set a size limit for investments, which means even a fairly large energy project could try to utilize it).

- Environmental Considerations: Energy projects in mountains often pose environmental issues – hydropower can affect river ecology, wind farms can impact bird migration or natural vistas. The law’s permitting flexibility (overriding local land-use plans) could inadvertently allow energy installations in places previously deemed off-limits (like near protected areas or on pristine rivers). If EIA requirements are respected, these impacts should be assessed, but there is concern that the political desire to realize projects quickly might pressure authorities to greenlight energy projects with insufficient mitigation. Albania has faced criticism in the past for a proliferation of small hydropower concessions without adequate environmental safeguards. This law could either exacerbate that (by opening more remote rivers to development) or improve it (by formalizing and scrutinizing the projects under a centralized body, which could apply stricter standards than some local governments did). A lot hinges on KKTU’s approach – if KKTU includes environmental ministry input, it could ensure compliance with EU environmental standards for energy projects (such as the Water Framework Directive’s no-deterioration principle, which requires maintaining river health). In summary for energy: the Mountain Package is a double-edged sword – it can stimulate renewable energy investment and contribute to energy diversification in line with EU climate goals, but it must be managed to avoid uncompetitive practices and ecological harm.

Impact on Tourism and Investment

Tourism is explicitly mentioned as a target sector for this law[4], and more broadly, the law aims to encourage all kinds of sustainable investments in mountain economies. The impacts here include:

- Boosting Sustainable Tourism Development: Albania’s mountain regions (e.g. the Alps in the north, the uplands in the south and east) have untapped tourism potential – for adventure tourism, eco-tourism, cultural heritage tourism, etc. The law lowers two major barriers to tourism investment: land access and initial cost. Entrepreneurs (local or diaspora) who have family land in beautiful locations can now formalize it and potentially develop guesthouses, lodges, or tourist attractions. The tax exemptions for 10 years give a significant head-start to new tourism businesses, which often face a slow start-up period. This could make marginal projects viable and attract outside capital to partner with locals. Indeed, the government has framed the law as “a concrete step to support economic development of mountain areas and encourage the return of the diaspora”[60]. By simplifying the legal environment, the law may draw expatriates or investors who were previously hesitant due to unclear land titles or bureaucratic hurdles. If this translates into renovated village homes into inns, creation of trails, and other amenities, it could strengthen Albania’s tourism offering and create local jobs.

- Risk of Overdevelopment or Unsustainable Tourism: On the flip side, there is a loophole concern that unscrupulous investors might use the scheme to build in inappropriate places. For example, a large hotel complex or resort might be built on what was communal pasture or a fragile alpine meadow, simply because the local possessor and investor push it through under the special regime (bypassing local zoning that might have prohibited large structures). Without careful control, this could lead to environmental degradation (spoilage of landscapes that are themselves the asset attracting tourists) and social disruption (if local communities feel a big project is imposed on them without consultation). Sustainable tourism by EU standards means development should be in scale with the environment and local capacity. The law does emphasize sustainable investment[61], but it provides no specific criteria or limits on tourism developments. It will be incumbent on KKTU and relevant ministries (Tourism and Environment Ministry is noted as a stakeholder on the official info site[62]) to ensure that projects are evaluated for sustainability – perhaps by requiring an environmental and social impact study even if not mandated by law, for projects that could alter a small community. Best practices from EU countries like Italy or Slovenia for mountain tourism involve zoning for tourism accommodations, caps on building volume in sensitive areas, and involving local stakeholders in project design. Albania’s challenge will be to integrate those practices into this fast-track process. If done poorly, there could be a backlash (locals opposing developments, negative press about environmental damage) which in turn undermines the investment climate the law tries to foster.

- Loopholes for Speculative or Non-Transparent Activities: The law’s incentive structure – practically free land and no taxes for a decade – could attract not only genuine investors but also speculators. A speculator might pretend to propose a tourism project, obtain the land title, then hold onto it hoping to sell to a higher bidder later (perhaps outside the 3-year window or by doing a minimal build to satisfy conditions). They might exploit the fact that land values will likely increase in those areas once infrastructure (roads, utilities) improves due to multiple projects. Another scenario is using a fake “tourism” label to get approval for something else – e.g., constructing what is ostensibly a resort but in practice ends up as private luxury villas or a gated community that doesn’t really serve tourism. Because the law overrides local plans, one could imagine a real-estate development sneaking in under the guise of tourism or agriculture. To avoid this, authorities should define clearly what kinds of projects qualify. The Council of Ministers’ decision for each zone sets allowed activity types[41], which is a crucial control. If a zone is designated for, say, “eco-tourism and agriculture,” then a purely residential development shouldn’t be approved. Vigilance is needed to ensure investors don’t drift from the approved purpose once they have the land. It might be wise to include claw-back clauses in the sale contract beyond construction – for example, if the investor does not actually operate the declared business for a certain number of years, penalties or reversion could apply. The current law doesn’t explicitly require the activity to continue for 10 years (only that if they cease activity they’d lose ongoing tax exemptions). That means a resort could be built, get its usage permit, and then close or switch use; the owner would keep the land, only losing future tax breaks. While market forces discourage building something only to close it, the lack of a long-term use obligation could be a loophole for those who have other intentions (like using the facility for private purposes or as a front).

- State Aid and Competition in Tourism: Much like with energy, giving selective benefits to tourism projects could distort competition. Within Albania, existing hotels or tour operators outside these zones might feel it unfair that newcomers in mountain zones pay no VAT or profit tax – effectively making it hard to compete on price. However, one might argue those mountain businesses face other disadvantages (remoteness, higher transport costs, etc.) justifying the aid. Internationally, if foreign investors are involved, they may be getting a subsidy that could raise concerns under any future EU competition alignment. But until membership, this is more a perception issue than a legal one.

- Impact on Local Communities and Labor: From a sectoral perspective, new investments in tourism and agribusiness (another likely sector – e.g. dairy or fruit processing in mountain areas) will create jobs. The law explicitly hopes to increase employment and improve living conditions in these zones[63]. If successful projects take off, they could provide much-needed local employment, reducing migration pressure. The quality of those jobs will be important. Mountain tourism often offers seasonal or low-wage work; it will be important that labor laws (minimum wage, social insurance) are enforced so that the local workforce truly benefits. There is also a social inclusion angle: will investments be inclusive of women, youth, and minorities in those areas? The law is neutral on that, but local governments can encourage that project selection (when considering which requests to support) take into account community benefits, not just the investors’ promises.

- State Infrastructure Support: For any sectoral development to succeed, complementary public investment is needed – roads, electricity, broadband, water supply. The law by itself doesn’t fund infrastructure, but implicitly, if zones are declared and investors commit, the government may feel pressure to extend infrastructure to those sites. This is positive if it means remote villages finally get better roads or power (aligning with EU rural development practices of improving infrastructure). However, it could strain local budgets if too many projects come at once. Coordination with Albania’s regional development and infrastructure plans is necessary so that new tourism or energy sites are accessible and viable. The worst-case scenario would be an investor builds a facility but it underperforms or fails due to lack of basic infrastructure or market access – leading to white elephants. To avoid that, feasibility scrutiny at the permit stage is key: KKTU and ministries should evaluate whether the proposed investment is realistic (e.g., building a 100-room hotel in a village with no road or known tourism demand might be a red flag of either unrealistic planning or perhaps an ulterior motive). Aligning projects with the national tourism strategy and regional plans will help ensure investments are coherent and sustainable.

Land Use, Rural Development and Property Rights

While not a traditional “sector,” the broad area of land use and rural development is at the core of this law’s impact, bridging multiple sectors:

- Land Consolidation and Use Efficiency: A positive impact anticipated is that previously idle or underutilized land will be put to productive use. Mountain areas in Albania often suffer from fragmented land parcels, abandonment (due to migration), and unclear ownership which deters investment. By clarifying ownership and enabling consolidation (an investor might partner with several adjacent possessors to create a larger project), the law can lead to more efficient land use. Larger contiguous plots allow for economies of scale in agriculture or tourism (e.g. creating an integrated agri-tourism farm). This aligns with EU rural development goals of land consolidation and combating fragmentation. In fact, the law explicitly mentions “consolidation of property relations” as one of its aims[64]. Over time, formalizing titles in these areas can also enable farmers to access credit (using land as collateral) or EU IPARD funds (which require clear land ownership for grants).

- Rural Development and Demographics: The law could help reverse rural decline if it succeeds in creating economic opportunities. By targeting mountain zones (which typically are poorer and have lost population), it reflects a spatially targeted development policy much like EU cohesion policy which directs support to less developed regions. If new businesses and infrastructure emerge, rural communities may stabilize or even see returnees (the government specifically hopes diaspora or emigrants might return to invest or work[60]). This can have spillover benefits: reduced pressure on cities from internal migration, preservation of cultural landscapes, and a rejuvenation of local traditions (some investments might be in crafts or traditional products for tourism).

- Property Rights Strengthening: Formalizing ownership for possibly thousands of possessors is a major strengthening of the rule of law in land governance. It will bring those lands into the cadastre system, provide legal security to people who have lived in uncertainty, and potentially reduce local land conflicts. As titles are issued, it will also make future transactions easier – sales, inheritances, or leases can happen in the formal market rather than informally. This can unlock economic value and is a step toward meeting EU standards for property rights (which are assessed in accession under the chapter of fundamental rights and judiciary). That said, one must watch for any social equity issues – who gets the titles? If it’s mostly men (since historically patriarchal norms might list the male as the “possessor”) there may be a gender gap. Ensuring that women’s rights (e.g. joint marital property or inheritance claims) are respected in the process is important for equitable development.

- Local Governance and Capacity: The law entrusts municipalities with substantial roles, which will impact the development of local institutional capacity. Municipalities will gain experience in land verification, public outreach, and managing development proposals. This is good for decentralization in the long run, building skills that align with EU practices of local planning and community-led development. However, in the short term, the complexity of the process might strain smaller rural municipalities that have limited staff and expertise. They must handle mapping, legal vetting, community consultations, and then later possibly monitor the projects. The central government will need to support them, possibly through the Agency for Support of Local Governance (which is already involved, as seen by the guidance issued and the dedicated “Mountain Package” portal[65][66]). Effective implementation will likely require training local officials and perhaps assigning expert teams (surveyors, legal advisors) to assist on the ground. If done well, this capacity-building is a net gain for rural governance; if not, inconsistent execution could hamper the law’s impact.

- State Aid in Agriculture/Rural context: In terms of EU alignment, transferring land to those who already use it can be seen as a form of social justice or completing agrarian reform. Many EU countries had land distribution or restitution programs historically – Albania’s is coming later for the mountain areas. As long as it’s one-time and aimed at development, it may not be controversial. The tax breaks might conflict with EU rules if they were long-term, but since they’re time-limited (10 years) and capped (500 cases)[3], they resemble a pilot program. EU rural development funds often provide grants up to certain amounts for farm or tourism investments; what Albania offers is arguably even more generous, but if it produces sustained businesses that eventually pay taxes after 10 years, it could pay off. The key is ensuring these businesses survive to that point – capacity building for entrepreneurs (how to run a guesthouse, how to market products) might be needed alongside the law, or else some investments could fail once the initial holiday period ends.

In conclusion, the sectoral impacts are broadly positive in intention – energy development, tourism growth, and rural regeneration. The law removes many impediments to those goals. Yet, implementation will determine whether these sectors truly benefit or face new challenges. It will be important to monitor early cases: for example, the first energy project or first resort under this scheme will set precedents. If they show strong community benefit, environmental care, and economic viability, confidence in the law will grow. If they result in controversy or problems (say, an environmental incident or a community protest), it will signal the need to adjust the approach (perhaps tightening criteria or enforcement). Flexibility and learning-by-doing, within the framework of the law, may be necessary to maximize its positive sectoral impacts.

Environmental and Social Impact

The Mountain Package law operates at the intersection of development and conservation, and it has significant environmental and social implications. These implications must be carefully weighed to ensure that the pursuit of economic growth does not come at an unsustainable cost to nature or communities.

Environmental Consequences and EU Standards Compliance

Albania’s mountain ecosystems – forests, rivers, alpine meadows – are among its most valuable natural assets. They provide biodiversity habitats, carbon sinks, and ecosystem services (like water provision) that are critical both locally and in a broader European context (many mountain areas are candidate Natura 2000 sites as Albania moves toward EU environmental network designation). The law acknowledges the importance of ecosystem protection in words[21], but its practical impact could put pressure on the environment:

- Land Use Change and Habitat Impact: By enabling construction and new activities in areas that were previously undeveloped, the law will inevitably lead to land use changes. Forested or wild land might be cleared for building tourist facilities, access roads, or small industrial plants. Pastures might be fenced or built upon. Each such change can fragment habitats and threaten flora and fauna. For example, mountain Albania is home to species like the Balkan lynx, bears, and various endemic plants; poorly planned development could encroach on their territories. Compliance with EU environmental directives would require assessing and mitigating these impacts. Under the Habitats Directive (though not legally binding yet for Albania, but instructive), any project likely to significantly affect a protected site must undergo an Appropriate Assessment and prove no adverse effect on site integrity[67][68]. Albania has national laws for protected areas and environmental impact – these need to be stringently applied in Mountain Package projects. If, for instance, a development zone overlaps with a proposed national park or a critical wildlife corridor, authorities should arguably exclude those sensitive parts from buildable areas. The law as written did not explicitly carve out protected areas or high conservation value zones from eligibility, which is a concern. It would be prudent, perhaps via the implementing regulations, to state that no project under this law is allowed in IUCN Category I/II protected areas or other critical zones, unless it’s demonstrably conservation-friendly (like eco-lodges with very small footprint and full environmental clearance).

- Environmental Assessment Procedures: The centralized permitting by KKTU could be a double-edged sword environmentally. On one hand, it might ensure that a national-level view is taken, potentially considering broader environmental policies (whereas a small municipality might ignore them for local gain). On the other hand, if KKTU decisions are driven by economic objectives from the top, they might override local environmental concerns. It is crucial that Albania’s Ministry of Tourism and Environment be involved in KKTU deliberations for these projects, and that EIAs (Environmental Impact Assessments) are not bypassed. Under Albanian law (aligned with Directive 2011/92/EU), certain developments require an EIA with public consultation and ministry approval. The Mountain Package law does not exempt projects from EIA – thus a hotel over a certain size, a hydropower plant, a mining activity, etc., still must go through that process. Enforcement is key: any attempt by investors to skip EIA citing the special status of the zone must be resisted, or Albania would fall afoul of fundamental EU environmental principles. Additionally, strategic environmental assessment (SEA) might be warranted if an entire zone development plan is created. It’s notable that the law required a Council of Ministers decision detailing allowed activity types in the zone[41] – this is effectively a small-scale spatial plan, which ideally should undergo some environmental screening.

- Water and Natural Resources Use: Many mountain projects will involve water (for tourism, agriculture irrigation, or especially energy). Overuse or diversion of water can harm downstream communities and aquatic ecosystems. The inclusion of “Water” in the KKTU’s title hints that water-use permits for such projects might be granted concurrently. EU Water Framework Directive standards would caution against any project that causes deterioration of water bodies. If multiple small hydros cluster in a region, cumulative impacts must be assessed – something Albania has been critiqued on in the past. A robust environmental oversight, possibly requiring cumulative impact assessments when multiple projects in a zone are considered, would align with EU best practices.

- Positive Environmental Opportunities: It’s not all risk – the law could also enable positive environmental outcomes if steered properly. For example, by giving locals ownership, it might incentivize better land stewardship. A family that gains title to its forest plot might be more inclined to manage it sustainably or reforest parts because they have secure tenure (as opposed to open-access state land which can lead to tragedies of the commons like illegal logging). The law also could encourage eco-tourism projects that actively conserve nature (like setting up guided parks, wildlife observation points, etc., which create an economic rationale to protect species). The mention of “efficient use of natural resources”[21] suggests that projects should ideally use resources like wood, water, or land in a way that isn’t wasteful. One could imagine supporting mountain agro-forestry or solar-powered facilities – aligned with EU’s green transition goals. To harness this, perhaps criteria or incentives for green investments within the scheme could be introduced (for instance, faster approval for projects with renewable energy use, waste management plans, etc.).

- Monitoring and Enforcement: A major environmental concern is whether Albania’s institutions have the capacity to monitor the new projects’ compliance with environmental conditions. In remote areas, enforcement is traditionally weaker. If a project is approved with certain mitigation measures (say, wastewater treatment for a tourist lodge, or fish passages for a hydropower plant), ensuring those are actually implemented and maintained will be challenging. Under EU law, there’s an increasing trend to involve local communities and NGOs in monitoring (e.g., environmental NGOs often help oversee compliance with nature protection commitments). Albania could channel this by fostering community-based monitoring – empowering locals to report environmental violations by any project. This ties into social trust: if the community sees that a new development is polluting a river or blocking access to a mountain trail, there must be accessible avenues to complain and get action. Otherwise, resentment will build and the law will be seen as privileging investors over the environment and public interest.

Social Impacts: Communities, Labor, Inequality, and Public Trust

The social dimension of the Mountain Package is significant, as it directly affects property rights, local community dynamics, and socio-economic equity:

- Local Communities and Customary Practices: The law essentially formalizes what has been informal for decades. In doing so, it may alter community relations. Traditionally, mountain communities had their own unwritten rules about who could use what land (often guided by custom or kinship). Formal titling might disrupt some of these arrangements – for better or worse. On one hand, it could reduce local conflicts by clearly delineating ownership (no more ambiguity over a plot’s status). On the other hand, if not handled sensitively, it might create winners and losers: those who manage to get recognized as owners vs. those who thought they had rights but failed to qualify. An inclusive approach by municipalities – identifying all genuine users and perhaps promoting co-ownership or cooperative structures where appropriate – can mitigate feelings of injustice. The social fabric in small villages is tight; the process of picking who is the “possessor” for a given piece of land could stir rivalries if not transparent. The 45-day notice allows villagers to speak up, which is good, but beyond legal claims, there might be ethical claims (“my family also grazed cattle there for years”). The law doesn’t provide a solution for shared use scenarios aside from whoever applies first and meets criteria. Municipalities may need to mediate these cases or encourage communal investment projects as an alternative.

- Employment and Labor Conditions: If the law succeeds in attracting new enterprises (farms, lodges, processing facilities, renewable plants), job creation is a primary benefit. Particularly, it could provide opportunities for underemployed youth in villages or for women who can work in hospitality, handicrafts, etc., linked to these investments. However, a critical factor is ensuring these jobs are decent and fairly paid. There’s a risk that some investors might view the 10-year tax holiday as a chance to maximize profit and could cut corners on labor costs or safety. Albanian labor law applies everywhere, but enforcement in remote areas is hard. Ensuring that labor inspectors visit these new businesses and that workers are aware of their rights will be important to truly improve local livelihoods. If done right, it might even reduce out-migration: people might stay if they can find reliable work locally.

- Preventing Inequality and Elite Capture: Social equity is a concern. While the law is ostensibly for everyone in the mountain zones, those with more knowledge, influence, or capital are in a better position to benefit. For example, a local elite or returning diaspora member with money can more easily draft a development project and navigate the bureaucracy than a subsistence farmer with little education. There is a risk that wealthier outsiders or local big men might end up capturing the most valuable lands and opportunities, leaving poorer villagers as bystanders or at best low-level employees. To counter this, the government (possibly through local councils or a supervisory board) could prioritize or support projects that have community co-ownership or clear community benefits. Also, providing technical assistance to smaller local entrepreneurs to develop bankable project proposals would level the playing field. Without such measures, the gap between haves and have-nots in rural areas could widen – which would be ironic given the law’s goal to uplift these regions comprehensively.

- Public Trust and Perception: The social acceptance of the Mountain Package will depend on whether people see it as fair and delivering on promises. Initially, there seems to be optimism – the law was presented with much fanfare, highlighting its bridging of customary and legal rights and its benefits to locals[6][2]. If early cases show a family obtaining title to their grandfather’s land and building a successful guesthouse, it will be a beacon story boosting trust in the government’s initiative. Conversely, if news emerges of a politician’s associate grabbing a scenic plot and doing something controversial, it will breed cynicism and possibly resistance. The government should thus be very transparent about early successes and failures, and be seen as responsive to concerns. Incorporating feedback and quickly addressing any unfair outcomes (for instance, if a mistake is made and someone’s claim was wrongly denied or a wrong person approved, there should be a mechanism to correct it) will show good faith. Social impact isn’t just jobs and income; it’s also psychological – giving mountain communities a sense that they are finally being heard and supported by the state, after years of marginalization. This law has the potential to increase public trust in the rule of law if done correctly, because people will tangibly see the law working for them (a title deed in hand, a new business opening). That’s a significant social outcome in itself in a country where trust in institutions has historically been low in remote regions.

- Preventing Social Displacement: One worry in development projects is displacement – people being forced to move or losing access to resources. The law’s approach is to give land to those already occupying it, so it’s not about expropriating anyone for projects (that’s a plus compared to many development scenarios). However, there could be indirect displacement: if an investor partners with a possessor to build, say, a resort on a piece of land that villagers used to cross or graze animals on, the community might feel a loss of a communal resource. Public notice might not fully capture such issues because no one “owned” that path or pasture legally. This can be mitigated if new developments are planned with community input – e.g., ensuring traditional footpaths remain open or that villagers get continued grazing rights on unused parts of a property. Social impact assessments, while not mandated, would be wise for larger projects to identify and address these kinds of issues proactively. In EU practice, even private developments often engage with local communities as stakeholders (sometimes voluntarily, sometimes due to regulatory pressure). Encouraging that approach here – say, an investor holds a town hall meeting to explain the project and listen to concerns – would help maintain social harmony.

- Cultural and Heritage Impact: Mountain areas in Albania are rich in cultural heritage (traditional architecture, archaeological sites, unique customs). New development could both support and threaten this heritage. If managed well, investors might restore old stone houses into guesthouses, or support local festivals to attract tourism – reinforcing cultural identity. If managed poorly, there’s a risk of culturally inappropriate construction (e.g., large modern structures that clash with the landscape) or commodification of culture in a way that locals resent. The law doesn’t address cultural heritage protection, but Albania has laws on cultural monuments that would still apply. Any project affecting a cultural monument needs special permission. Authorities should ensure that in the rush to develop, they don’t approve something that demolishes or alters a site of cultural significance. Again, involving the Ministry of Culture or relevant institutions when screening projects in historically sensitive areas would align with EU standards (which emphasize preserving cultural heritage as part of sustainable development).

In summary, environmental and social impacts are intertwined in the Mountain Package’s implementation. The law presents an opportunity for a win-win: revitalized communities living in harmony with a preserved environment, exemplifying sustainable development. But it also poses a threat of environmental degradation and social discord if its provisions are abused or if development overtakes conservation. Aligning with EU environmental standards (through rigorous impact assessments and respect for protected areas) and fostering inclusive social practices (ensuring broad community benefit and participation) are essential to tip the balance toward positive outcomes. The government will need to be vigilant and perhaps ready to refine the approach as lessons emerge from initial projects. Sustainable mountain development is a delicate art – Albania now has a powerful tool to shape it, and with that comes the responsibility to ensure that economic gains do not erode the natural and social capital that make mountain regions worth developing in the first place.

Overall Assessment and Risk Summary

Overall, Law 20/2025 “Për Paketën e Maleve” represents a bold and innovative attempt to address entrenched problems of Albania’s mountain regions through a mix of property legalization, economic incentives, and streamlined governance. It aims to unlock the potential of these areas by formalizing land tenure and attracting investment, while also safeguarding public interest goals like environmental protection and social development. In this concluding assessment, we summarize the law’s key strengths and risks, and suggest safeguards and recommendations to bolster its positive impact and mitigate downsides:

Key Strengths of the Decree

- Legalization and Rule of Law: The law directly tackles the legal vacuum that has long existed in mountain property rights. By bridging customary usage with formal ownership, it brings many properties into the legal fold, thereby reducing informality. This enhances the rule of law in a very practical way – people who were de facto owners gain de jure recognition, which can reduce disputes and increase respect for law in these communities. In the long term, this legal clarity lays the groundwork for better governance (e.g., accurate cadastral records, proper taxation after the holiday period, and easier inheritance). Notably, it does so in a way that honors local reality (10+ years of possession) rather than imposing from above, which is a sensitive and sensible approach.