Albania’s oil and gas industry has a long and complex history that dates back to the early twentieth century. During World War I, in September 1917, the Italian government became particularly interested in Albania’s natural riches, awarding some of the first concessions for their use. In the decades that followed, businesses from the UK, France, Russia, and other countries were interested in Albania, intending to develop its oil and gas extraction industry.

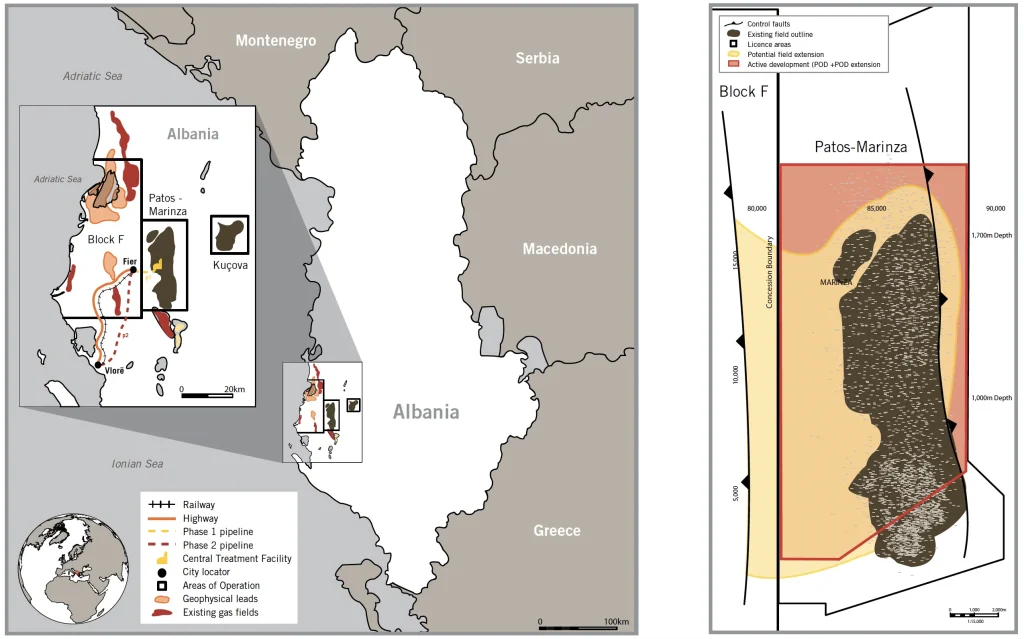

When the Albanian government started talks with the British company Premier Oil in 1993, a new era after the fall of communism began. As a result, an agreement to develop the Patos-Marinza oil field was signed in 1994. As part of the agreement, Premier Oil and the state-owned Albpetrol sh.a formed Anglo-Albanian Petroleum, a joint venture that was charged with managing operations at one of Europe’s biggest onshore oil fields, Patos-Marinza.

In addition to starting research and investigations, Premier Oil’s experts worked on some of the Patos-Marinza wells that were operational. This company kept up its operations until 2004, when it unexpectedly left Albania after ten years of involvement.

But less than a month after the withdrawal, a new company, Saxon Energy International, was registered in the Cayman Islands. And two months later, it signed an agreement with Albpetrol sha and took the place of the British company Premier Oil in Patos-Marinza oil field.

Although Premier Oil had only formally withdrawn, it had registered in the Cayman Islands tax haven, merely changing its name and posing as a Canadian business in the interim. The representative, Richard Uofsorth, who had been in Albania since 2001 to oversee Premier Oil’s Patos-Marinza project, remained the same.

The problem was that the Albanian government of the time under Prime Minister Fatos Nano ignored the hydrocarbon law, which states that in these cases of agreements, the company must have experience and submit the balance sheets of the last 5 years. The agreement was ‘blessed’ by the minister of the time, Viktor Doda.

Three years after its founding, Saxon Energy International decided to change its name and became Bankers Petroleum, which is also the name of its parent company in Canada.

Because the business was registered in the Cayman Islands, its owners were shielded and also enjoyed tax exemptions. Since there is no corporate income tax on profits, capital gains, or dividends, companies in this nation function more like middlemen, purchasing the “product” from one company and reselling it to another.

In the contract signed with Premier Oil in 1994, the division of oil production was 15% for Albpetrol sh.a (Albanian state oil and gas company) and 85% for Premier Oil, while in the contract signed in 07/06/2004, AlbPetrol sh.a received only 1% gross overriding royalty (ORR) on new production, while Saxon or Bankers Petroleum received 99%.

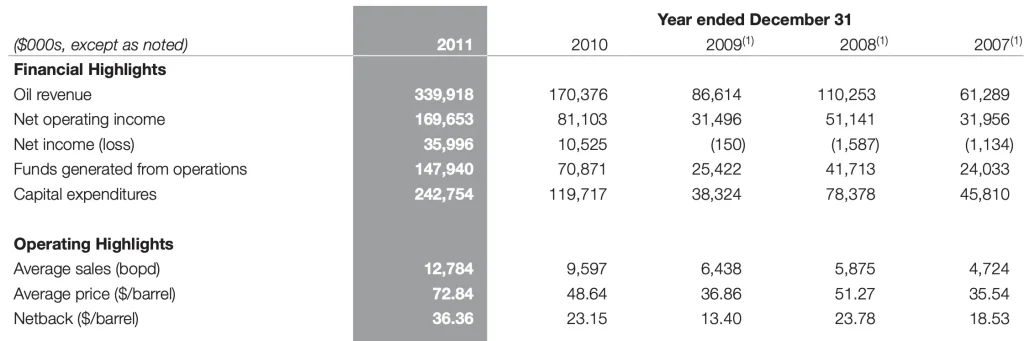

Reports from first 10 years later showed that Bankers Petroleum Ltd had paid 0 profit tax and for 2013 alone, the company’s revenue was over $540 million.

In 2006, then-Minister of Economy Genc Ruli signed a development plan with Bankers Petroleum, which outlined that the cost recovery phase would conclude in 2009. From that point forward, the company was expected to begin paying profit tax to the Albanian state. However, this obligation was never fulfilled.

The critical question remains: Why did the Albanian government allow this deviation to go unchecked for so long, without initiating any enforcement or corrective action?

Bankers Petroleum Albania and Genc Ruli, the then-Minister of Economy, worked together to revise the “Petroleum and License Agreements” in 2008. The modification significantly decreased Bankers Petroleum’s long-term tax obligations in Albania by enabling the business to exclude royalties from future income taxes.

In the same year, the company added retired U.S. General Wesley Clark, who led Operation Allied Force during the Kosovo War and served as NATO Supreme Allied Commander, to its board of directors. Many saw the action as a calculated attempt to protect the company’s business interests in Albania and exert political pressure on the government.

This again avoided paying the profit tax, but at least, the government of the time made Bankers Petroleum pay the mining royalty, 10% royalty tax (RT) on net production.

Things changed again with the arrival of the socialist government and Prime Minister Edi Rama, on June 23, 2013, when Bankers Petroleum was added three taxes: Excise Tax, Turnover Tax and Carbon Tax.

This came after the Rama first government decided to heavily tax the hydrocarbon sector and the concession companies did not have to make an exception. The agreement was reviewed, and the necessary modifications were made. But did Bankers Petroleum started paying taxes?

Although the 2008 amendment to the “Petroleum and License Agreements” allowed Bankers Petroleum to offset royalty payments against future income taxes—effectively reducing its projected tax burden—this provision was further reinforced years later. In 2015, the AKBN National Agency of Natural Resources ( Agjencia Kombëtare e Burimeve Natyrore ), under a decision issued by then-Minister Damian Gjiknuri, officially classified these three key taxes as “hydrocarbon costs.” This designation allowed Bankers Petroleum to fully recover those costs—100%—from oil production revenues, effectively nullifying the expected fiscal contribution.

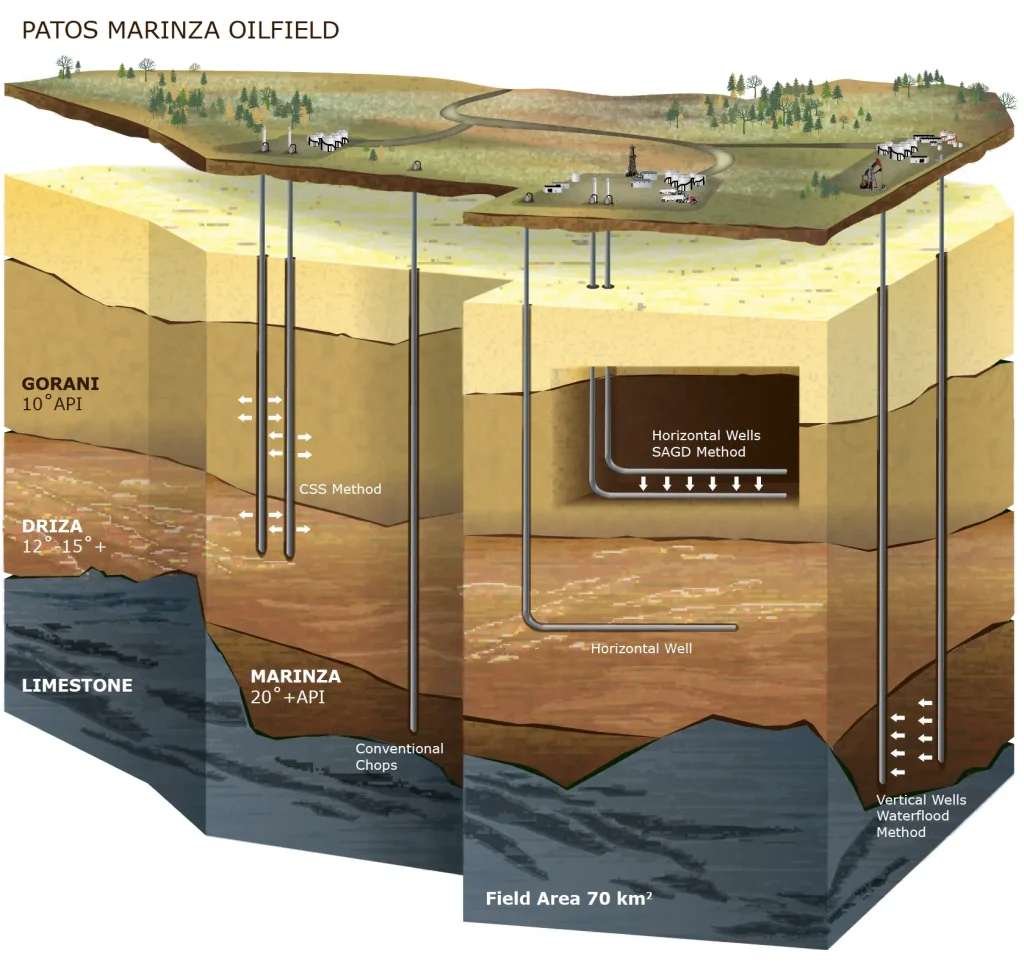

Throughout its operational period, Bankers Petroleum has consistently reported using approximately 20% of its net oil production for diluent injection—a process required to optimize extraction in its heavy oil fields. This technical justification, included in the company’s official filings with the National Agency of Natural Resources (AKBN), has been used to support large volumes of tax-exempt fuel imports.

However, investigations and market observations suggest that a significant portion of this imported commercial fuel—initially declared for operational use—was instead diverted into the domestic market. Through local partners, including BOLV Oil, this fuel reportedly entered Albania’s monopolized fuel sector without being subjected to any taxes or duties.

Estimates indicate that this practice may have resulted in the evasion of hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes, raising serious concerns about regulatory oversight, enforcement, and the broader implications for public revenue.

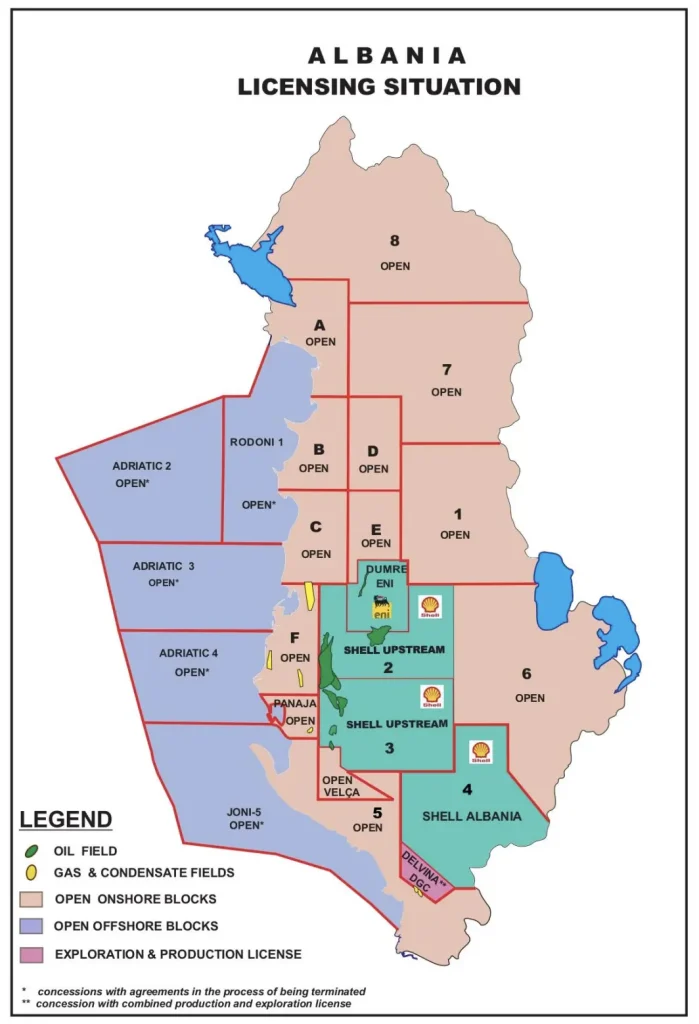

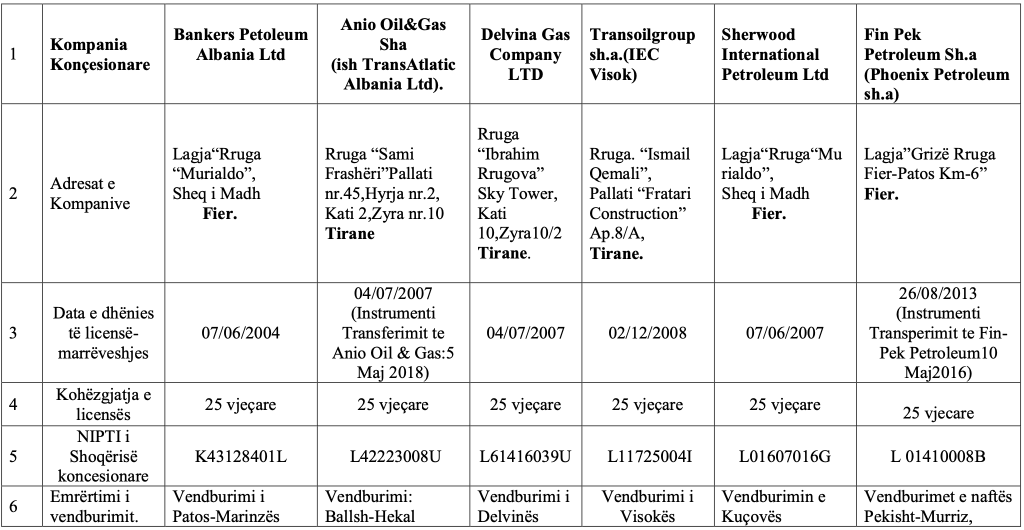

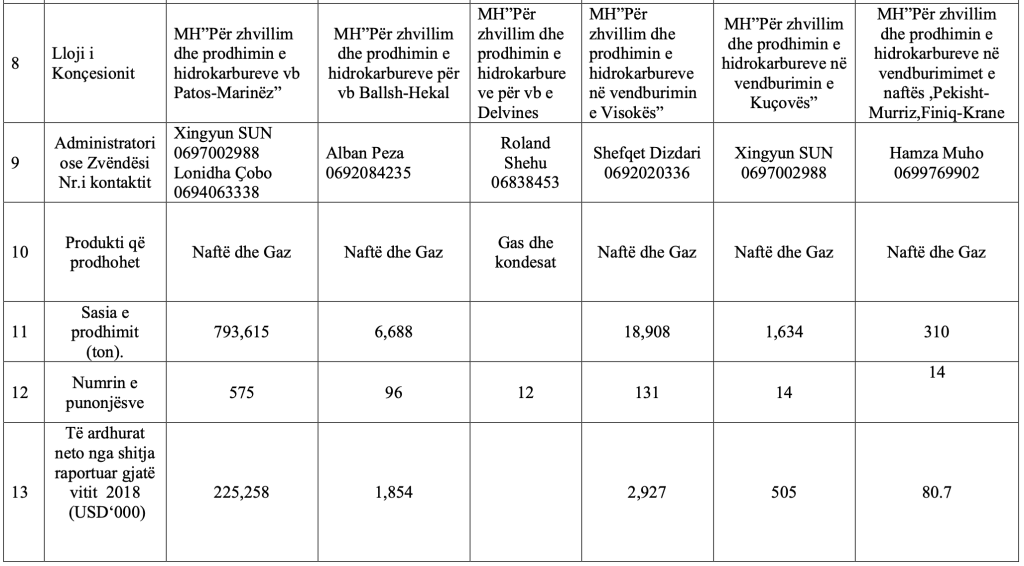

All subsequent agreements signed by the Albanian state with companies in the hydrocarbon sector followed a similar model to the one established with Bankers Petroleum. In 2008, the government entered into a production-sharing agreement with Stream Oil for the Ballsh, Gorisht, and Koçul oil fields—an arrangement that mirrored the same unfavorable terms, leaving the Albanian state with limited benefits from its own natural resources. Notably, Stream Oil was registered in the Cayman Islands, raising further concerns about transparency and accountability.

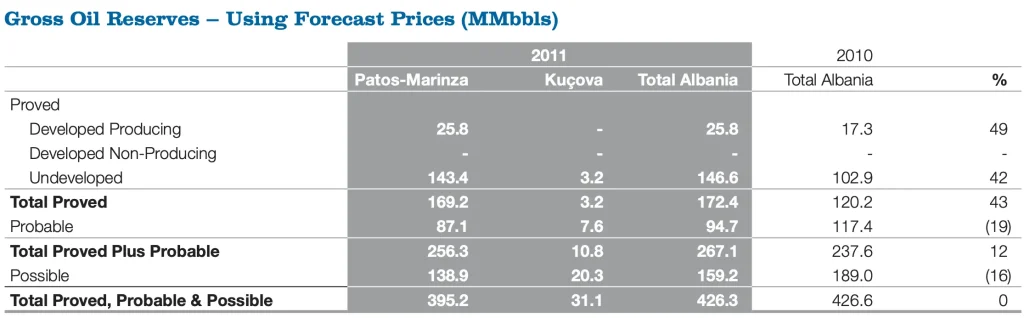

A similar pattern emerged in Kuçova, where the rights were granted to Sherwood—a company that, despite operating independently on paper, was in fact owned by Bankers Petroleum. Like Stream, Sherwood was also registered in the Cayman Islands, reinforcing a trend of offshore-registered entities operating Albania’s key oil fields under opaque corporate structures.

Albpetrol sh.a. has also come under scrutiny for a lack of transparency, particularly in its dealings with state oversight institutions. The company reportedly refused to provide the Albanian Supreme Audit Office with access to contracts concluded with private oil companies, citing confidentiality clauses as justification for withholding key information. This deliberate obstruction has raised serious concerns about accountability and the oversight of public resources in the country’s hydrocarbon sector.

In 2016, a significant shift occurred in Albania’s oil sector when Bankers Petroleum came under Chinese ownership. The company publicly announced that it had entered into a definitive agreement with “1958082 Alberta Ltd” and “Charter Power Investment Limited” for the acquisition of all outstanding shares of Bankers Petroleum Ltd at a price of $2.20 per share. Both purchasing entities were subsidiaries of Geo-Jade Petroleum Corporation , one of China’s largest independent oil and gas exploration and production companies.

The transaction, structured under the laws of the Canadian province of Alberta, valued Bankers Petroleum at approximately $575 million, excluding liabilities. This marked a major turning point, placing one of Albania’s most strategic energy assets under Chinese corporate control.

But a year before the sale was finalized, the owners of Bankers Petroleum sued Albania in International Arbitration after requesting that $236 million be recognized as expenses, all amounts generated from the production of the Patos Marinza field through the cost recovery procedure.

Through a notice, the Ministry of Energy announced at the time that the arbitration had stated that the costs claimed by Bankers were rejected and declared irrecoverable. Therefore, the state is not obligated to recognize this value.

Following this decision in favor of the Albanian state, Bankers Petroleum was obligated to begin paying profit tax on its operations. Under hydrocarbon contracts like Bankers’, the applicable profit tax rate is 50%. Accordingly, on revenues exceeding $236 million, a thorough audit was to be conducted to verify actual costs and determine the company’s true tax liability to the Albanian government.

However, recent reports indicate that Bankers Petroleum has once again failed to meet its tax obligations, paying little to no profit tax to the state—significantly less than what is owed.

Prosecutors in Fier, Albania announced 14 security actions, including 9 arrests. Five foreign nationals are still at large. Bankers Petroleum CEO Hongping Xiao and former director Leonidha Çobo were arrested during a raid on the company’s offices. The six-month investigation, which began in December 2024, alleges that the company falsified financial reports, inflated operating costs, and laundered funds through a network of contractors in order to consistently declare losses and benefit from fraudulent VAT refunds — all while avoiding corporate income tax.

Between 2004 and 2024, Bankers Petroleum reported over 532 billion lek in revenue (approx. €5 billion). However, according to investigators, the company simultaneously declared losses and avoided paying a single euro in profit tax, exploiting a controversial clause in its concession agreement known as the “R-Factor.”

The allegations brought against Bankers Petroleum executives include “creation of fraudulent VAT schemes,” “concealment of income,” “money laundering,” “abuse of office,” and “failure of tax authorities to perform duties.” These are the result not just of the company’s internal operations, but also of suspected coordination with contractors and potentially complicit tax officials. To prevent evidence tampering, prosecutors took corporate data and personal devices during raids earlier this week. According to insiders, the inquiry is broadening to include offshore benefactors and contractor networks that contributed to financial imbalances.

Even more alarming, the corporation recorded €800 million in net profits, including €110 million in only the previous two years, despite stating that it had yet to return its investment. Critics believe that this is due to manipulative accounting and overstated expenditure declarations, which are supported by a labyrinth of offshore firms and favourable contractor connections. The Supreme State Auditor (KLSH) had warned for years that the R-Factor had been altered, but no action was taken.

Why did it take the Albanian government and prosecutors so long to take action, despite these facts being known since the early stages of Bankers Petroleum’s operations?

The most serious issue with the “Bankers” case besides the overdue tax debt or the standard balance-sheet manipulation. These are unquestionably significant criminal violations. The central issue of this case is the true ownership of the oil wells, as well as the destiny of billions of euros taken from Albanian underground without leaving a trace in the public budget.

The same method has been used for all the country’s natural wealth and industrial assets: demolition, transfer into unknown hands, use as a means of developing, sale, and silence. All of Albania’s natural resources are in the hands of invisible shells, as are the industrial assets.

The prime minister Rama government seems to have indicated that it intends to hand over management of the Patos-Marinza oil field to other lobbying groups as the license that Bankers Petroleum currently holds is about to expire. This is allegedly an attempt to discredit Chinese interests. Corruption, and geopolitical factors are thought to be the main drivers of this change, which is reminiscent of other contentious attempts like the stated offer of Sazan Island, a National Natural Park, to US President Donald Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, for the construction of luxurious hotels.

Bankers Petroleum a social-environmental bomb.

Although capitalism has gained ground, the region of Ballsh and Fier seems to be stuck in the past, environmental issues seem secondary, neglected, profit and the black legacy of the past erases them and has turned into an apocalyptic landscape of the oil region. Poorly managed oil and inadequate extraction technology which results also in explosion of wells, leave behind polluted lakes and destroyed rivers.

Residents of the Patos-Marinza area have expressed major concerns about environmental degradation caused by protracted oil extraction activity. Local water wells have apparently become toxic, leaving the town without access to safe drinking water, as oil appears to have contaminated the groundwater. In many regions, soil health has been irreversibly harmed—the land was rendered black by oil, leaving it unsuited for agriculture or livestock.

Air quality has also deteriorated due to industrial pollution, and the surrounding environment is littered with abandoned oil tanks, rusted equipment, leaking pipelines, and pools of stagnant oil. The outcome is a once-inhabitable countryside that residents now characterize as essentially unlivable, with consequences for not only the environment but also the social structure of entire communities. Despite these circumstances, Bankers Petroleum has demonstrated a stunning lack of corporate social responsibility (CSR), failing to address even the most fundamental environmental concerns in its business locations.

By Ranier della Vecchia